Published in Lana Turner | A Journal of Poetry and Opinion no.14

What I’m afraid of most of all is lest I become a „poet.“

After the publication of her first book, Three Clicks Left (1978) — which went through numerous editions in a short time and sold over 40,000 copies, something only Yannis Ritsos or Odysseus Elytis had previously managed to do — the Greek anarchist poet Katerina Gogou (1940-1993) became the object of police surveillance. Her apartment was searched several times over the years. At demonstrations, she was openly threatened and repeatedly arrested. Three Clicks Left describes the struggles in which she was significantly involved. Together with Idionymo (1980), The Wooden Overcoat (1982), and The Absent Ones (1986), it reflects a revolutionary, militant period in Greece.

Gogou was born in Athens in 1940. The early years of her life were marked by the resistance to the German occupation during World War II and the Greek Civil War (1946-1949). In the 1950s she attended a number of theater and dance schools. She appeared in film and theater productions early on. In 1977 she starred in the film The Heavy Melon, directed by her husband Pavlos Tassios, which depicted the struggles and experiences of a new urban working class. At the Thessaloniki Film Festival she won the award for best screenplay for her her work on the film Ostria (1984), directed by Andreas Thomopoulos. Over the years she received several awards for her exceptional performances in films. In 1980 she starred in Parangelia! (again directed by Pavols Tassios), reciting poems from Three Clicks Left and Idionymo to the music of composer Kyriakos Sfetsas.

The fall of the military junta (1967-1974) accelerated the end of the authoritarian dictatorship and ushered in a transitional period (Metapolitefsi) that notably included the extremely brutal suppression of the student uprisings at the Athens Polytechnicum in November 1973. Gogou condemned Konstantinos Karamanlis’s orientation of the country towards Western-style neoliberal capitalism. A large part of the population continued to be excluded from economic participation, while in the shadows a powerful and predominantly far-right apparatus of military, police, and conservative groups ruled.

The language of Gogou’s poetry — immediate, angry, and marked by deep sensitivity — deconstructs bourgeois moral concepts and describes everyday life in Greece in the 1980s as infected by a creeping totalitarianism. Gogou addresses a network of Marxism, anarchism, and feminism. A member of anarchist associations and Trotskyist groups, she distrusted the Communist Party of Greece, which during the years of the university occupations in 1979-80 brutally suppressed the students‘ aspirations for autonomy, including the right to resist police violence.

„I said endurance has its limits, people are made of flesh and bone / I spoke about the Stalinists and the method of executing the very best as traitors who died screaming LONG LIVE THE PARTY! / Sifis said / the statement is only the beginning. Then they will ask Who are your friends. / Then Where do they live.“ (56)

The present collection of Katerina Gogou’s work — excellently translated by A.S. and published by fmsbw — comprises seven volumes of poetry originally published in Greek by Kastaniotis press — a significant supporter of Gogou’s work, even when she doubted herself.

In her books, she drew a map of the left-politicized milieu of outsiders and the lumpenproletariat of the neighborhoods and streets of Athens — places like Exarcheia, Metaxourgeio and Patisia. She identified with the people who were humiliated and marginalized by a patriarchal society. Her work renewed the kind of class memory composed out of the confrontations with the state’s mechanisms of oppression.

„Our life is pointless panting / at pre-programmed strikes stooges and patrol cars. / That’s why I’m telling you. / Next time they’ll let us have it / we shouldn’t run. We should hold our line. Let’s not sell our asses so cheap, man. / Don’t. It’s raining. Gimme a smoke.“ (11)

Gogou writes in the context of feminist movements of the 1970s that encouraged women across Europe to break out of the tight corset of a centuries-old „social contract“ maintained through subtle forms of everyday oppression. Her radical feminist revolt was manifested in political actions and attacks:

„WHEN GOD THROWS A THUNDERSTORM WITH HAIL AND A DOWNPOUR SHE COMES OUT TO THE STREET HAVING NO SOX ON SHE WHISTLES TO MEN THROWS STONES AT PATROL CARS… TO ALL PATROL UNITS. ATTENTION, ARMED. DANGEROUS. ARMED. DANGEROUS. / THEY CALL HER SOFIA VICKI MARIA OLIA NIKI ANNA EFI ARGYRO AND SHE IS BEAUTIFUL BEAUTIFUL BEAUTIFUL BEAUTIFUL, MY GOD.“ (65)

In „Family Origin“ her rage is aimed at her father’s dominance and violence. The title recalls Friedrich Engels The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, which demonstrates the derivation of the patriarchal family from the exigencies of bourgeois property relations. Gogou writes:

„You bloody bastard, I’ve got you. […] I blow the smoke like nails / into your faded old-man’s eyes […] And I standing up on that chair with that same stupid bow. / That one self-same fear. / 5 years old. 19 years old. 20. 30. / All my life, dad.“ (20)

„Father, Say Something, Talk to Me,“ from her last book of poems, The Seventh Book, planned as a poetic autobiography and published posthumously in 2002, describes in detail the humiliations and painful moments she experienced during her childhood under the tutelage of her father and why she finally left home at the age of thirteen, spending nights on the street with homeless alcoholics. The poem is an indictment that explains how she, too, became a „warrior“ due to the circumstances of her upbringing and very quickly „learned guerrilla tactics,“ „the art of warfare.“

Gogou always considered violence to be a legitimate means of achieving change in the context of political struggle. She tried to redefine the terms „terror“ and „violence,“ not leave them to the propaganda of the state. Thus she recorded in the collection The Month Of The Frozen Grapes (1988):

„Terrorism. I dominate through Violence and Terror. / And what does terrorist mean? / I don’t want an answer from those who invented it. / I look for an answer from those gasping from running“ (159)

In 1986, she stated in an interview: „I am in the position of fighting … And if they think I’m a terrorist, let them do so.“

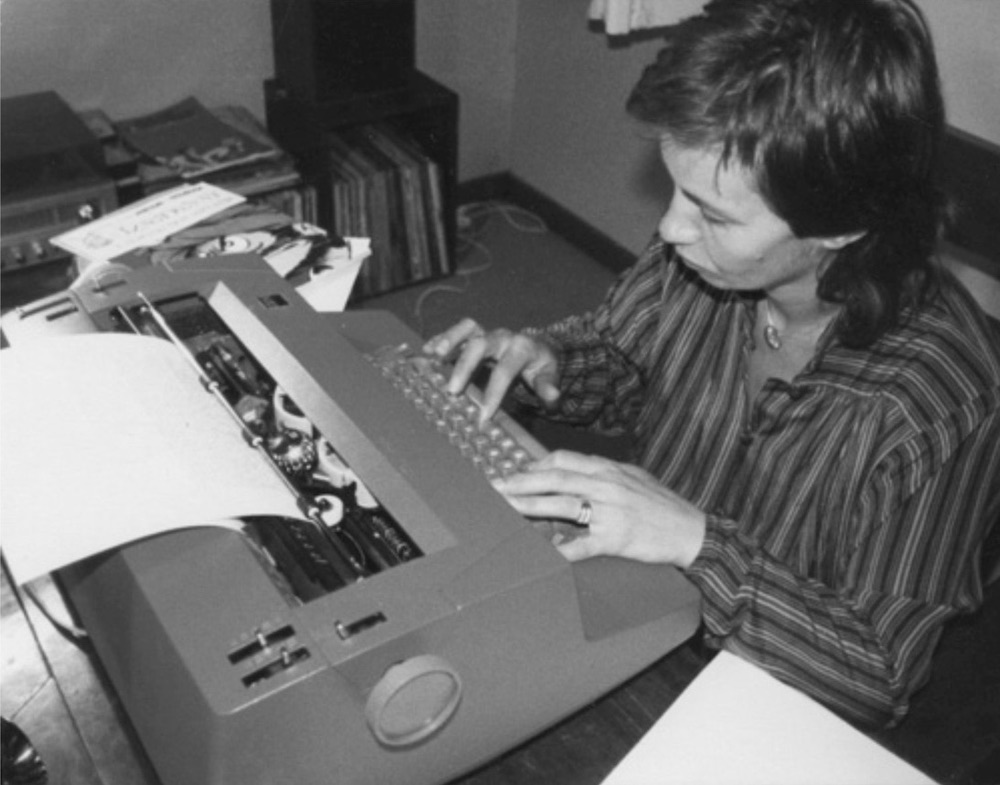

The poems of the last years are a critical commentary on her life, written between hospitalizations, persistent depression, and worries about her daughter Myrto. With each successive book, the urgency to write about the loss of solidarity within society and the disappearance of friends into prisons or psychiatric wards increases. Her focus is on a doubting, retrospective self. In an interview she says that she writes in order not to go crazy. She is fascinated by those who have chosen the path of no return. Loneliness and pain; memories, cries, tears. She hammers on her typewriter with a cigarette burning in the ashtray.

In one of her most fascinating poems, „Autopsy Report 2.11.75,“ from the volume The Wooden Overcoat (1982), Gogou revisits the day when the Italian poet Pier Paolo Pasolini (he was certainly more than an ally to her) was found murdered on the beach at Ostia. In the blind spot of a surveillance camera, Gogou traces in detail Pasolini’s agonizing death.

„His face disfigured by the framework of the class he denied / a black and blue volunteer of the ragtag proletariat. / The fingers of the left hand broken by social realism thrown away to floodlit trash. / The jaw broken / by the uppercut of a union organizer a hired thug. The ears chewed by a sonofabitch / who couldn’t get an erection. / The neck broken and severed from the body on the basic principle of independent function.“ (75).

She points out the „parallel connection“ between the Vatican and the PCI (and their co-responsibility), which saw the homosexual poet as a nuisance, one finally silenced by henchmen.

The books of Katerina Gogou had a considerable influence on the British anti-fascist poet Sean Bonney (1969-2019), who frequently engaged with the work of revolutionary, political poets, such as Hölderlin, Lautréamont, Aimé Césaire, Pasolini, Amiri Baraka and Diane di Prima. In Our Death (Commune Editions, 2019), Bonney’s first book published in the United States, the section „Cancer: Poems after Katerina Gogou“ presents a rewriting of her work, moving the struggles and conflicts from 1980s Athens to post-Thatcher London and the Berlin of the present. Like Gogou, Bonney demonstrates how poetry can position itself as a counter-history to official political statements. He captures the original energy of Gogou’s texts, the language of terror. He draws an „obscene angle“ to Gogou’s „AUTOPSY REPORT“— which is indebted to Rimbaud’s „psalm about current events“ — by connecting Pasolini’s broken finger with the fascist cops from the G8 summit in Genoa, where 23-year-old Carlo Giuliani was killed by a shot to the head and run over twice by a police car:

„as when in Gogou’s poem the blows of his murderers become identical with different forms of art, with the Vatican and with the hired thugs who split his name apart one night in the 1970s. […] Someone razored his fingerprints away, in the way refugees do to themselves, and they kept them in an office in City Hall.“ (Our Death, 49)

„Will it get to the addressee? […] Do you remember me? They call me Katerina. […] My hair’s grown longer, the middle finger of my left hand is broken and a big burn scar from a chopper-bike exhaust still remembers“ (Gogou, Poems, 244)

„now let’s see what you’re gonna do…“

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar