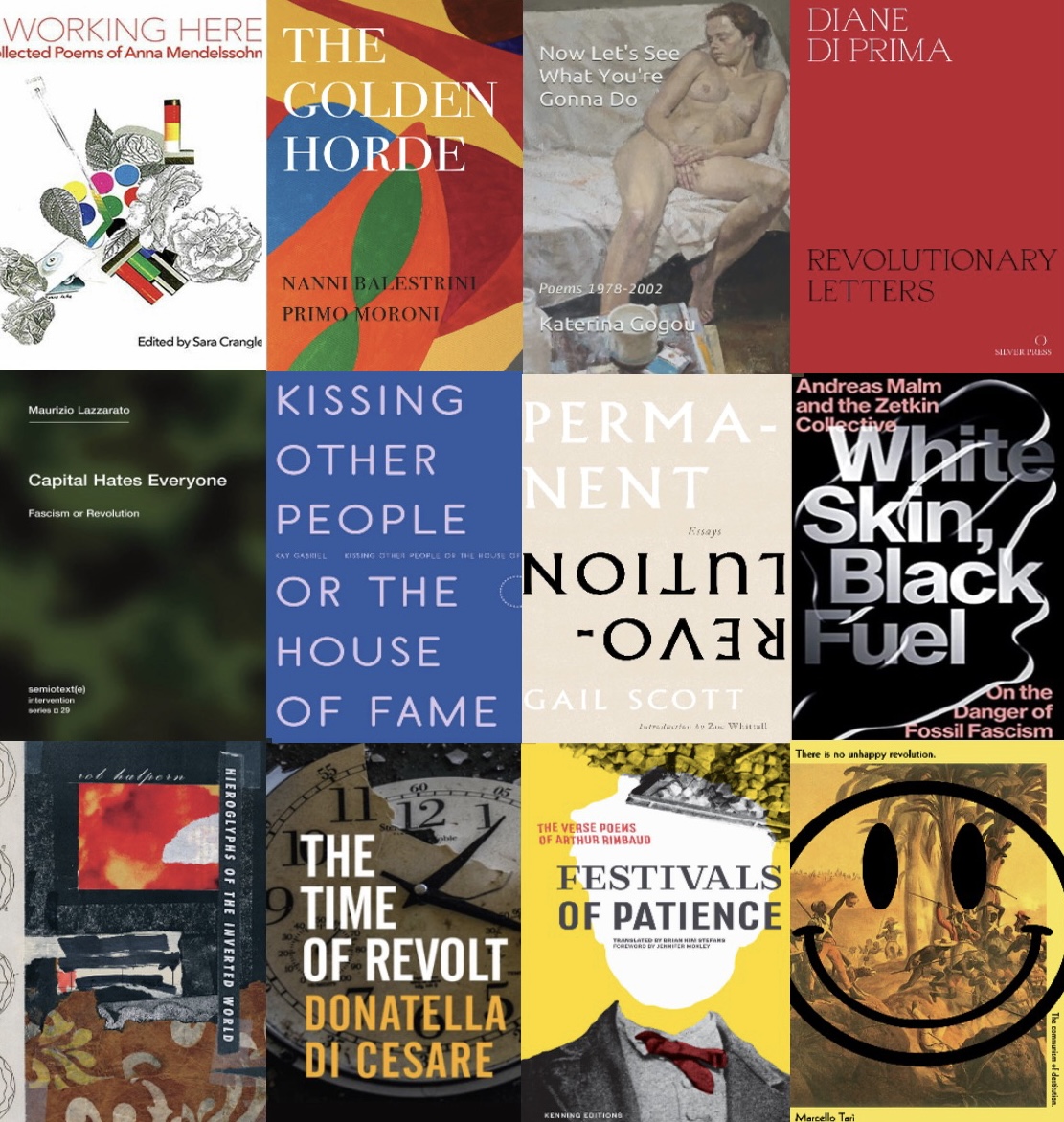

Nanni Balestrini, Primo Moroni | The Golden Horde. Revolutionary Italy, 1960-1977

Translated by Richard Braude [Seagull Books]

The Golden Horde is a definitive work on the Italian revolutionary movements of the 1960s and ’70s. An anthology of texts and fragments woven together with an original commentary, the volume widens our understanding of the full complexity and richness of this period of radical thought and practice. The book covers the generational turbulence of Italy’s postwar period, the transformations of Italian capitalism, the new analyses by worker-focused intellectuals, the student movement of 1968, the Hot Autumn of 1969, the extra-parliamentary groups of the early 1970s, the Red Brigades, the formation of a radical women’s movement, the development of Autonomia, and the build-up to the watershed moment of the spontaneous political movement of 1977. Far from being merely a handbook of political history, The Golden Horde also sheds light on two decades of Italian culture, including the newspapers, songs, journals, festivals, comics, and philosophy that these movements produced. The book features writings by Sergio Bologna, Umberto Eco, Elvio Fachinelli, Lea Melandri, Danilo Montaldi, Toni Negri, Raniero Panzieri, Franco Piperno, Rossana Rossanda, Paolo Virno, and others, as well as an in-depth introduction by translator Richard Braude outlining the work’s composition and development.

The Golden Horde is a definitive work on the Italian revolutionary movements of the 1960s and ’70s. An anthology of texts and fragments woven together with an original commentary, the volume widens our understanding of the full complexity and richness of this period of radical thought and practice. The book covers the generational turbulence of Italy’s postwar period, the transformations of Italian capitalism, the new analyses by worker-focused intellectuals, the student movement of 1968, the Hot Autumn of 1969, the extra-parliamentary groups of the early 1970s, the Red Brigades, the formation of a radical women’s movement, the development of Autonomia, and the build-up to the watershed moment of the spontaneous political movement of 1977. Far from being merely a handbook of political history, The Golden Horde also sheds light on two decades of Italian culture, including the newspapers, songs, journals, festivals, comics, and philosophy that these movements produced. The book features writings by Sergio Bologna, Umberto Eco, Elvio Fachinelli, Lea Melandri, Danilo Montaldi, Toni Negri, Raniero Panzieri, Franco Piperno, Rossana Rossanda, Paolo Virno, and others, as well as an in-depth introduction by translator Richard Braude outlining the work’s composition and development.

Katerina Gogou | Now Let’s See What You’re Gonna Do [fmsbw]

Translated by A.S.

What I’m afraid of most of all is lest become a “poet.”

After the publication of her first book, Three Clicks Left (1978) — which went through numerous editions in a short time and sold over 40,000 copies, something only by Yannis Ritsos or Odysseus Elytis managed to do — the Greek militant poet Katerina Gogou became the object of police surveillance. Her apartment was searched several times over the years. At demonstrations, she was openly threatened and repeatedly arrested. Three Clicks Left, as well as Idionymo (1980), The Wooden Overcoat (1982) and The Absent Ones (1986) reflect a revolutionary, militant period, describing the struggles and squats in which Gogou was significantly involved. [from my forthcoming review]

Anna Mendelssohn | I’m Working Here. Collected Poems [Shearsman Books]

Anna Mendelssohn was also an activist, born into a highly politicised family. Her father Morris was a respected Labour councillor and a former Communist who fought with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Her mother, Clementina, was a member of the Manchester International Women for Peace, and took an active part in the family business, a local market stall. After the 1958 founding of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Mendlesons participated in its annual marches. The family’s Jewish heritage was central, defining: an archived certificate confirms that to mark the occasion of her first birthday, Mendelssohn’s parents had three trees planted in Israel in their daughter’s name. Mendelssohn visited an Israeli kibbutz in the mid1960s, and occasionally attributes her later poetry to variants of her Hebrew name, Channa Nechama Enna Krshner Mendleson Lubovitch bas Hakolenian. During World War II, Mendelssohn’s mother volunteered to care for refugee Jewish children, some rescued from Nazi concentration camps, and this harrowing experience was often recounted to Mendelssohn and her younger sister Judi. Both parents were forced to leave school for employment in their early teens, but they were intellectually ambitious for their offspring: newspaper clippings of Mendelssohn’s childhood achievements indicate that she grew up in a cultured household, learning Hebrew and French, entering music and elocution contests, performing in local theatre productions and with the Manchester Youth Orchestra, and becoming Head Girl at Stockport High School for Girls. In her life writings, Mendelssohn often describes, with palpable bitterness, the exacting, relentless criticisms of her parents, with special attention paid to her father’s domineering political drive. Her home environment grated and inspired.

Anna Mendelssohn was also an activist, born into a highly politicised family. Her father Morris was a respected Labour councillor and a former Communist who fought with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Her mother, Clementina, was a member of the Manchester International Women for Peace, and took an active part in the family business, a local market stall. After the 1958 founding of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Mendlesons participated in its annual marches. The family’s Jewish heritage was central, defining: an archived certificate confirms that to mark the occasion of her first birthday, Mendelssohn’s parents had three trees planted in Israel in their daughter’s name. Mendelssohn visited an Israeli kibbutz in the mid1960s, and occasionally attributes her later poetry to variants of her Hebrew name, Channa Nechama Enna Krshner Mendleson Lubovitch bas Hakolenian. During World War II, Mendelssohn’s mother volunteered to care for refugee Jewish children, some rescued from Nazi concentration camps, and this harrowing experience was often recounted to Mendelssohn and her younger sister Judi. Both parents were forced to leave school for employment in their early teens, but they were intellectually ambitious for their offspring: newspaper clippings of Mendelssohn’s childhood achievements indicate that she grew up in a cultured household, learning Hebrew and French, entering music and elocution contests, performing in local theatre productions and with the Manchester Youth Orchestra, and becoming Head Girl at Stockport High School for Girls. In her life writings, Mendelssohn often describes, with palpable bitterness, the exacting, relentless criticisms of her parents, with special attention paid to her father’s domineering political drive. Her home environment grated and inspired.

Like so many of her generation, Mendelssohn became the first member of her family to attend university. From 1967 to 1969, she studied Comparative Studies at the University of Essex. Opening its doors in 1964, Essex quickly became a notoriously radical hub: although the English Department was set up in large part by the conservative, prominent Movement poet Donald Davie, in its early days Ed Dorn was a lecturer and Tom Raworth was a poet in residence. In spring 1968, influenced by Situationism, student activism, and the general strike in France, Essex was shut down due to a protest against a visiting speaker from Britain’s Porton Down, the world’s oldest chemical weapons research facility. Mendelssohn was involved in this protest, and in the same year, took part in large-scale London marches against the Vietnam War. At Essex, she campaigned to be elected to the National Union of Students, was a member of the Theatre Arts Society, and wrote. She appeared with a group of students in the conclusion of Jean-Luc Godard’s documentary on student unrest in England, British Sounds (1969); from under the brim of an out-sized orange felt hat, she argues for properly controversial counter-lyrics to the Beatles’s curiously resigned “Revolution”, beaming and hesitating before the camera, and accompanying the music with some rather accomplished playing of a kazoo. Still enrolled at Essex, Mendelssohn travelled to Turkey in 1969, teaching English and French to schoolchildren in Ankara, and possibly associating with members of the Turkish National Liberation Front. In 1970, she returned to London, where she wrote for countercultural periodicals and agitated on behalf of squatters’ rights whilst working to move homeless people into unoccupied London council blocks. At this time, she describes herself as emotionally vulnerable: in mourning for a friend who had recently died in a motorcycle accident, and at perpetual odds with her politicised associates who chastised her for her devotion to writing. A long poem about London – now apparently lost – was her particular focus. This antagonism places Mendelssohn within a lengthy historical trajectory of vanguardists deemed traitors for privileging art over action. As these domestic conflicts came to a head, a friend of Mendelssohn’s suggested that she might be happier living with some people she had known at Essex. Mendelssohn appears to have made this move willingly, but claims, forevermore, to have been coerced – “seized”, “arrested” – to remain with her new housemates, who were affiliated with the urban guerrilla organisation known as The Angry Brigade. Mendelssohn’s American contemporaries in extremist activism – among them, Jane Alpert, Susan Stern – similarly liken their involvement in clandestine organisations to incarcerations. Like Mendelssohn, these women found their lives irretrievably marked by associations that oscillated between the utopian and the dystopian. In her archive, Mendelssohn recounts bitterly and repeatedly how she “‘became known (with much revulsion) as the Angry Brigade girl.’” (from the Introduction by Sara Crangle)

Marcello Tarì | There Is No Unhappy Revolution: The Communism of Destitution

Translated by Richard Braude [Common Notions]

“The commune is invariably in the tradition of the oppressed—from the Anabaptist communities of Münster, through the Paris Commune of 1871, right down to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and the global movement of 1968. It has resurfaced across the globe, from the Oakland docks to Taksim Square in Turkey, without forgetting that last appearance of the alter-globalization countersummits in 2007—against the G8 in Rostock, Germany—marked an important change of strategy for movements at an international level. The International Brigades signed their communique to the riot that began the real summit with the slogan: “Long live the commune of Rostock and Reddelich!” And thus the road was prepared.

“The commune is invariably in the tradition of the oppressed—from the Anabaptist communities of Münster, through the Paris Commune of 1871, right down to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and the global movement of 1968. It has resurfaced across the globe, from the Oakland docks to Taksim Square in Turkey, without forgetting that last appearance of the alter-globalization countersummits in 2007—against the G8 in Rostock, Germany—marked an important change of strategy for movements at an international level. The International Brigades signed their communique to the riot that began the real summit with the slogan: “Long live the commune of Rostock and Reddelich!” And thus the road was prepared.

Colectivo Situaciones began their analysis of the Argentinian insurrection with a significant theoretical gesture, defining it not as a large-scale social movement or a political practice (however extraordinary) but instead as an “ethical operation.” Knowing how to make this distinction between social movement, political practice, and ethical operation is no easy exercise, given how much we are used to putting homogeneous labels of “movement” and “politics” on an extremely diverse array of events and processes, without any clarity as to what these words might even mean. In reality, if one reflects on these terms well, one sees that social movements—those we discuss at least—only exist when there is neither an insurrection nor a revolution underway. A social movement can march through cities and perhaps block the streets, occupy houses, and, if it is strong enough, even declare a strike—but in an insurrection a people is born, in a revolution a class is constituted. It represents an existential storm for whoever enacts it. And then there are events—such as those in Notre-Dame-des-Landes or the Susa Valley, the Kurdish communes in Rojava and the Zapatista ones in the Lacandon Jungle—that cannot be thought of in terms of social movements. In truth, these are revolutionary experiences in which autonomy, dwelling, and self-organization are already here.”

Festivals of Patience: The Verse Poems of Arthur Rimbaud

Translated by Brian Kim Stefans [Kenning Editions]

Parisian War Song

Parisian War Song

It is evident Spring’s here, for / the verdant Estates hold wide / agape their amazing splendors / with the flight of Thiers and Picard! // Oh May! What delirious asses! / Sèvres, Meudon, Bagneux, Asnières, / listen now to the trespasses / that strew their spring-like cheers! // They have shakos, sabers, tom-toms, / not the old candle boxes, / and skiffs that have not ev-… ev-… um? / split lakes of bloodstained waters! // More than ever, we drink and dance / when, clambering our ant-warrens, / the yellow crania collapse / in these extraordinary dawns! // Thiers and Picard are twin Erotes / and thieves of heliotropes. / They paint Corots with petrol; / here, beetling about, are their tropes. // They’re friends with the Grand Whozit! / —Favre, lounging in gladiolas, / blinking, weeps an aqueduct, / —his sniffles produce a pepper! // The Big City’s cobbles are hot / in spite of your rains of oil; /and, decidedly, it’s time that we / shuffle you up in your roles… // And the Rustics who find solace / in long, luxurious squattings, / will hear, among red rustlings, / boughs in the forests snapping.

Donatella Di Cesare | The Time of Revolt

Translated by David Broder [polity]

As capitalism triumphs on the ruins of utopias and faith in progress fades, revolts are breaking out everywhere. From London to Hong Kong and from Buenos Aires to Beirut, protests flare up, in some cases spreading like wildfire, in other cases petering out and reigniting elsewhere. Not even the pandemic has been able to stop them: as many were reflecting on the loss of public space, the fuse of a fresh explosion was lit in Minneapolis with the brutal murder of George Floyd. We are living in an age of revolt.

As capitalism triumphs on the ruins of utopias and faith in progress fades, revolts are breaking out everywhere. From London to Hong Kong and from Buenos Aires to Beirut, protests flare up, in some cases spreading like wildfire, in other cases petering out and reigniting elsewhere. Not even the pandemic has been able to stop them: as many were reflecting on the loss of public space, the fuse of a fresh explosion was lit in Minneapolis with the brutal murder of George Floyd. We are living in an age of revolt.

But what is revolt? It would be a mistake to think of it as simply an explosion of anger, a spontaneous and irrational outburst, as it is often portrayed in the media. Exploding anger is not a bolt from the blue but a symptom of a social order in which the sovereignty of the state has imposed itself as the sole condition of order. Revolt challenges the sovereignty of the state, whether it is democratic or despotic, exposing the violence that underpins it. Revolt upsets the agenda of power, interrupts time, throws history into disarray. The time of revolt, discontinuous and intermittent, is also a revolt of time, an anarchic transition to a space of time that disengages itself from the architecture of politics.

Kay Gabriel | Kissing Other People or the House of Fame [Rosa Press]

“STOFFWECHSEL”

“STOFFWECHSEL”

rudely I am, Andy, addled with cold and this is an occasion / say for naps and dreaming as it turns out I dreamt about you, / the occasion of my poem, which is the reason for telling you / the epiphany of a poem called STOFFWECHSEL / this poem was by you in fact it was penned in your hand / it showed the evidences of your formal niceties say / deliberate refusal to break the line on / a fifty-cent word like “niceties” / indeed the cheeriest philologues could have / established to a skeptical audience it was indeed / your poem written by you / which you read to me by my feverish bed / in which I dreamt (U.S. English “dreamed”) / of things like STOFFWECHSEL / the Frankfurt am Main wannabes’ theoretical / centerpiece I’d prefer at a wedding or sickbed / Andy get ready for the good part / though I pause in relating the poem / to take Advil and water to continue relating the poem / called “STOFFWECHSEL” in which you intoned / GET UP POET IT’S TIME TO INGEST YOUR THEORY / the capital letters hammering even on the Starbucks / windows of my stuffy nose GET UP POET you said again / IT’S TIME TO INGEST YOUR THEORY / at which point conveniently there appeared in the poem / Advil and a glass of water to hand / the debt to Eliot is clear, even those / cheeriest of philologues agree: / Andy, your poem is superior / Eliot chose not to supply the reader with any / non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at all / or acetaminophen, yours is an apothecary / more receptive to business which is how it comes that / this poem “STOFFWECHSEL” / is among other things manifestly yours not Tommy’s / David’s or even Kay’s / not written by the four-piece suit / I metabolize nothing it comes right back / out with a child’s persistence / Andy I tumbled out of the dream into the insistence / of a whole bottle of Advil I will never again have a headache this Feb. / a month in any case when I shall bear up in hopes of / the epiphany of your poem redux / the instructions on the bottle stipulating it is to be taken with food / toast e.g. or flavored ice or oyster crackers, say / in the Stoffwechsel of the age I’m feeling good enough to hurry up

Before that I am bound uptown on a train with Stephen and a woman / friend of his, he asks if it’s worthwhile to read Brecht and it’s weird cause / I thought he was part of a big Brecht festival I had just seen but in fact it / was a circus, we head there next. I end up having to sleep next to a squid / on land, who secretes some sticky black-brown liquid like molassess, it gets / on my feet and maybe I have to eat it. A picture of Stephen and his friends, / who are pets like Christopher Robin, attempting to carnivorize the squid / and its ragtag troupe of a small elephant and some other animals. The / faces of the pet-like ragged troupe are fixed in a mask of happy striving, / the fish look inscrutable. Then Stephen and his woman friend are in a play / I’m late to see, why didn’t I plan better // A bimbo-looking plastic hot clone of Lix gaymous we go to / a show and the clone and Lix meet but the clone steals their / necklace we drag them out of the movie theatre we never exit / instead deposit them at a lecture about the kidnapping which has / become famous in a book by Simone White, also it happened in / 1820 and I wake up crying for Kevin Killian (from the collection Kissing Other People or the House of Fame)

Maurizio Lazzarato | Capital Hates Everyone

Translated by Robert Hurley [Semiotext(e) / Intervention Series]

We are living in “apocalyptic” times, in the literal sense of the word—times that manifest, times that reveal. What they show, firstly, is that the financial collapse of 2008 initiated a period of political ruptures. The alternative “fascism or revolution” is asymmetrical, out of balance, because we are already inside a seemingly irresistible series of “political ruptures” created by neo-fascist, sexist, racist forces; because for the moment, the revolutionary rupture is just a hypothesis, dictated by the necessity of reintroducing what neoliberalism has succeeded in erasing from the memory, the action, and the theory of the forces combating capitalism. This is even its most important victory.

We are living in “apocalyptic” times, in the literal sense of the word—times that manifest, times that reveal. What they show, firstly, is that the financial collapse of 2008 initiated a period of political ruptures. The alternative “fascism or revolution” is asymmetrical, out of balance, because we are already inside a seemingly irresistible series of “political ruptures” created by neo-fascist, sexist, racist forces; because for the moment, the revolutionary rupture is just a hypothesis, dictated by the necessity of reintroducing what neoliberalism has succeeded in erasing from the memory, the action, and the theory of the forces combating capitalism. This is even its most important victory.

What these apocalyptic times also show is that the new fascism is the other face of neoliberalism. Wendy Brown confidently asserts a contrary truth: “From the viewpoint of the first neoliberals, the galaxy that includes Trump, Brexit, Orbán, the Nazis, or the German Parliament, the fascists in the Italian Parliament, is turning the neoliberal dream into a nightmare. Hayek, the ordoliberals, or even the Chicago school would repudiate the current form of neoliberalism and especially its most recent guise.” This is not only false from a factual standpoint, it is also problematic for understanding capital and the exercise of its power. By erasing the “violence that founded” neoliberalism, incarnated by the bloody dictatorships of South America, one commits a double, political and theoretical, error: one concentrates only on the “violence that preserves” the economy, the institutions, law, and governmentality—tested out for the first time in Pinochet’s Chile—and so one presents capital as an agent of modernization, as a power of innovation; moreover, one erases the world revolution and its defeat, which however are the origin and cause of “globalization” as the global response of capital.

The conception of power that results from this is pacified: action upon action, government upon behaviors (Foucault) and not action upon persons (of which war and civil war are the peak expressions). Power would be incorporated into impersonal apparatuses that exert a soft violence in an automatic way. Quite to the contrary, however, the logic of civil war that is at the foundation of neoliberalism was not absorbed, erased, replaced by the functioning of the economy, law, and democracy.

The apocalyptic times show us that the new fascisms are in the process of reactivating— although no communism is threatening capitalism and property—the relationship between war and “governmentality.” We are living in a period of blurring, of hybridization of the State of law and the state of exception. The hegemony of neofascism must not be measured simply by the strength of its organizations, but also by the capacity it has to bleed into the State and the political and media system.

The apocalyptic times reveal that beneath the democratic façade, behind the economic, social, and institutional “innovations,” one always finds the class hatred and violence of strategic confrontation. It only took a movement of rupture like the Yellow Vests, who have nothing revolutionary, or even pre-revolutionary, about them, for the “spirit of Versailles” to awaken, for a new upwelling of the desire to shoot those “pieces of shit” who were not threatening, even symbolically, power and property. When there is an interruption of the time of capital, even a bourgeois editorialist can grasp a bit of emergent reality: “The current empire of hate is resuscitating boundaries of class and caste, sometimes long dormant […]. One is seeing that acid of hate which eats away at democracy and suddenly submerges a decomposed, destructured, unstable, fragile, unpredictable political society—the ancient hatred resurfacing in the faltering France of the 21st century. Underneath modernity, hatred.”

The apocalyptic times also manifest the strength and weaknesses of the political movements which, since 2011, have tried to contest the supreme power of capital. This book was completed during the Yellow Vests uprising. Adopting the viewpoint of “world revolution” in order to read such a movement (but also the different Arab Springs, Occupy Wall Street in the U.S., the M15 in Spain, the days of June 2013 in Brazil, etc.) might seem pretentious or fantastical. And yet “thinking at the limit” means starting again not only from the historical defeat suffered in the 1960s by world revolution, but also from the “unrealized possibilities” which were created by and included revolutions, differently in the North and in the South, and which are still timidly mobilized in contemporary movements.

The form of the revolutionary process had already changed in the 1960s, but it had come up against an insurmountable obstacle: the inability to invent a different model from the one that, in 1917, had begun the long string of 20th century revolutions. In the Leninist model, revolution still had the form of realization. The working class was the subject that already contained the conditions of the abolition of capitalism and the installation of communism. The passage from “class in itself ” to “class for itself ” needed to be realized through the prise de conscience and the seizure of power, organized and led by the party that brought in from the outside what was lacking in the “tradeunion” practices of the workers.

Since the 1960s, however, the revolutionary process has taken the form of the event: political subjects, instead of being already there in the making, are “unforeseen” (the Yellow Vests are a paradigmatic example of this unforeseeability); they don’t embody history’s necessity, but only the contingency of political confrontation. Their constitution, their “coming-to-consciousness,” their program, their organization are formed on the basis of a refusal (to be governed), a rupture, a radical here and now that aren’t satisfied with any promise of democracy and justice to come.

To be sure, with all due respect to Rancière, the uprising has its “reasons” and its “causes.” The Yellow Vests are more intelligent than the philosopher, because they have “understood” that the relationship between “production” and “circulation” has been reversed. Circulation, the circulation of money, commodities, human beings, and information now takes precedence over “production.” They no longer occupy the factories, but the roundabouts, and attack the circulation of information (the circulation of currency being more abstract, targeting it requires another level of organization and action).

The precondition for the emergence of the political process is obviously a rupture with the “reasons” and “causes” that generated it. Only the interruption of the existing order, only the exit from governmentality will be able to open up a new political process, because the “governed,” even when they resist, are power’s double, its correlates, its opposite numbers. Rupture with the time of domination, by creating new possibilities, unimaginable before their appearance, establishes the conditions for the transformation of self and the world. But no mystique of the riot, no idealism of the uprising is called for.

The processes of constitution of the political subject, the forms of organization, the development of capabilities for the struggle, made possible by an interruption of the time of power, are immediately confronted with the “reasons” of profit, property, and patrimony which the uprising has not caused to disappear. On the contrary, they are more aggressive, they immediately invoke the reestablishment of order, placing the police at the forefront, while continuing, as if nothing had happened, the promulgation of “reforms.” Here the alternatives are radical: either the new political process manages to change capital’s “reasons,” or those same reasons will change it. The opening up of political possibilities is confronted with the reality of a formidable double problem, that of the constitution of a political subject and that of the power of capital, because the former can only take place within the latter. (from the Introduction)

Gail Scott | Permanent Revolution [Book*hug Press]

The term Permanent Revolution (the title of a work by Leon Trotsky) has its roots in Marxism; I have gleaned from it what I want for purposes of foregrounding prose experiment as crucial to those who identify as women; +, by extension, to proximate others on the ever widening scale of gender distribution. To recognize that gender minorities are—as are other diverse minorities—in a permanent state of emergency as concerns life + the expression of it is necessarily to reshape how we narrate as a species. A species that thinks, at least in part, back through our mothers. A living community is also a community of sentences, signing, in particular, our relationship to female ancestors.

The term Permanent Revolution (the title of a work by Leon Trotsky) has its roots in Marxism; I have gleaned from it what I want for purposes of foregrounding prose experiment as crucial to those who identify as women; +, by extension, to proximate others on the ever widening scale of gender distribution. To recognize that gender minorities are—as are other diverse minorities—in a permanent state of emergency as concerns life + the expression of it is necessarily to reshape how we narrate as a species. A species that thinks, at least in part, back through our mothers. A living community is also a community of sentences, signing, in particular, our relationship to female ancestors.

There is nothing that sets the scene better for this than Mina Loy’s feminist manifesto with its almost scornful call-out to women: “Is that all you want?” Rising in the professions, she warns, is not enough! “NO scratching on the surface of the rubbish heap of tradition will bring about Reform, the only method is Absolute Demolition.” I don’t have to agree with everything in that manifesto to see that Loy is on the right track in calling for fundamental change in the entire set of systems/institutions that impact us.

If the focus in my work was, up to the early 90s, an exploration of the question of the feminine in writing, the new + recast essays featured here are concerned with diverse notions of ‘Fe-male.’ They are a modest evolutionary snapshot of various approaches + concerns—notably class—in the writing of my later novels, work that was accompanied by my travelling the continent in search of other experimental prose writers working in English.

I am finalizing the collection in a dire period of pandemic, climate calamity, the continued police assassination of Black + Indigenous peoples, coupled with ongoing indifference regarding missing + murdered Indigenous women.

A writer must do as she can with her epoch. Rage accumulates. (from the Preface)

Diane di Prima | Revolutionary Letters [Silver Press]

You had a striking way of going ahead with poetry and other kinds of writing, putting aside even other things about life, and eventually even coming to a kind of spiritual type of writing. And you’re still moving in that direction.

You had a striking way of going ahead with poetry and other kinds of writing, putting aside even other things about life, and eventually even coming to a kind of spiritual type of writing. And you’re still moving in that direction.

Well, you know, it’s very interesting. It’s like at some point there started to be a couple of serial poems. They’d just go on and on and on. One is the Revolutionary Letters and one is Loba. And it’s like they’re the two strands — one is very pragmatic and one is this very, sometimes, very far-out geography of the female imagination. But whatever it is, it just inundated me one day and wouldn’t go away. Because very often I just hear a poem and I have to stop what I’m doing and write it. Sometimes I hear it. Or sometimes, with Loba, I carried around an image, literally a picture for months in different notebooks until the words came that went with it.

But some things I still worked on as if I was honing them, like some of the Revolutionary Letters I had to work on because they were like guerilla theater. The first ones happened without my having that plan in mind. I was in somebody’s house, babysitting a house in Los Angeles while I was waiting to find out whether or not somebody was going to buy a book of mine, for a movie, which of course never happened. But while I was there, I saw something on TV that got me so mad. It was about General Electric moving in on the Navajo Reservation. And it just happened at that point:

I have just realized that the stakes are myself / I have no other / ransom money, nothing to break or barter but my life / my spirit measured out, in bits, spread over / the roulette table, I recoup what I can

nothing else to shove under the nose of the maître de jeu / nothing to thrust out the window, no white flag

this flesh all I have to offer, to make my play with / this immediate head, what it comes up with, my move

as we slither over this go board, stepping always / (we hope) between the lines [Revolutionary Letter #1]

And then [the letters] got more practical — they talked about storing water in your bathtub, if you needed it. Because they turned off the water in Newark during one of the big riots and that was the biggest problem. We could get in on back roads. They had blockaded the roads. But we could bring food in, but we couldn’t figure out what to do about the water. And then [the questions] came: Can you own land? Can you own a house, own rights from other’s labor, stocks, or factories, or money loaned at interest? What about the yield of some crops, autos, airplanes dropping bombs? Can you own real estate so others pay you rent?

To whom does the water belong? To whom will the air belong, as it gets rare? The American Indians say that a man can own no more than he can carry away on his horse. And, you know, times went on. Things change. The letters kept changing with them. And there was a thing called the Liberation News Service, and I would give them bunches of letters whenever I wrote them. [LNS] would mail them out to all the newspapers that were free papers in all the big cities, about 200 of them. Even the Black Panther newspaper published one or two of my letters at one point.

But it’s like this really organized red kind of energy, like anarchist energy, and I said, “Mmm, I think I’m going to go to the country.” Plus, the FBI was at my front door every night, banging on the door. I was sending different kids to the door because everybody grown up at the table was wanted for the draft or wanted for something else. Yeah, it was really like that. (from Between the Lines”: A Conversation with Diane Di Prima | LARB)

Andreas Malm and The Zetkin Collective | White Skin, Black Fuel [Verso]

White Skin, Black Fuel is a much larger historical project than HtBUaP, because we wrote it as a group of twenty comrades. And we started back in summer 2018. It was a bit delayed because of the pandemic, and we ended up writing the last material in January of this year. In the first part of the book, we look at thirteen different countries in Europe and the US and Brazil and studied what the far right has done and said about climate and energy in the last two decades. The second part is an attempt to go deeper into the historical roots of this phenomenon. But the amazing thing about working together with this many people is that we know a lot of different languages in this group and therefore we’ve been able to draw out similarities and of course, differences between countries such as Hungary, Spain, Sweden, the US, Brazil, and so on.

White Skin, Black Fuel is a much larger historical project than HtBUaP, because we wrote it as a group of twenty comrades. And we started back in summer 2018. It was a bit delayed because of the pandemic, and we ended up writing the last material in January of this year. In the first part of the book, we look at thirteen different countries in Europe and the US and Brazil and studied what the far right has done and said about climate and energy in the last two decades. The second part is an attempt to go deeper into the historical roots of this phenomenon. But the amazing thing about working together with this many people is that we know a lot of different languages in this group and therefore we’ve been able to draw out similarities and of course, differences between countries such as Hungary, Spain, Sweden, the US, Brazil, and so on.

So, what does this research show in 2021? Donald Trump is no longer the president, which is a great relief from my horizon, at least. You can obviously have all kinds of criticisms about Joe Biden. But it’s certainly a setback for the global far right that Trump isn’t there any longer. He doesn’t exercise that magnetic pull that galvanized the far right in Europe and in places like Brazil any longer. But the far right is with us for sure. It’s extremely strong in a lot of countries in Europe, from France to Sweden to Denmark, as the last elections showed. And as temperatures continue to climb, the far right will still be defending the privileges that come with fossil fuel consumption. And that aggressive defense must be grappled with just as repression will have to be grappled with. Our book is an attempt to follow these lines in history and see how they have intensified in the past decade and where they might lead next. Ultimately, of course, our hope is that this will stimulate strategic discussions in the climate movement and in various anti-racist, antifascist movements around the world about how to battle this common enemy. That is, where is the far right and how can it be vanquished. Why is it that the far right so intensely defends fossil fuels and denies the climate crisis in one way or another? And where does this whole complex of racism and fossil fuels come from? When were they conjoined? (from An Interview with Andreas Malm, The New Inquiry)

Rob Halpern | Hieroglyphs of the Inverted World [Kenning Editions]

Rob Halpern’s new sequence of poems speaks to social, environmental, and personal crisis—from white supremacist violence and wildfires raging just north of San Francisco, to the death of his father—all of which are tempered by the joyful birth of his daughter, whose new life offers relief in the darkness. He calls the poems “hieroglyphs” with a tip of the hat to Marx, for whom the “hieroglyphic” appearance of the world translates “the secret” of our catastrophe. But as Halpern notes, “the secret of the thing may well be that there is no secret.” Here, investigation, analysis, and healing converge, as Hieroglyphs of the Inverted World tests the promise and the failure of cultural production, specifically lyric poetry, in the midst of disaster. In his afterword to the book, Halpern asks, “Can the moment arrested by the poem’s burnished amber show us something we don’t already know about the world?” And if not, what is the social function of the poem? Perhaps the question is unanswerable, but this book attempts a response.

Rob Halpern’s new sequence of poems speaks to social, environmental, and personal crisis—from white supremacist violence and wildfires raging just north of San Francisco, to the death of his father—all of which are tempered by the joyful birth of his daughter, whose new life offers relief in the darkness. He calls the poems “hieroglyphs” with a tip of the hat to Marx, for whom the “hieroglyphic” appearance of the world translates “the secret” of our catastrophe. But as Halpern notes, “the secret of the thing may well be that there is no secret.” Here, investigation, analysis, and healing converge, as Hieroglyphs of the Inverted World tests the promise and the failure of cultural production, specifically lyric poetry, in the midst of disaster. In his afterword to the book, Halpern asks, “Can the moment arrested by the poem’s burnished amber show us something we don’t already know about the world?” And if not, what is the social function of the poem? Perhaps the question is unanswerable, but this book attempts a response.