NANNI BALESTRINI (1935-2019)

I close my eyes and start to sing

threads are entangled and transformed into spots whose dance moves ever more slowly

I sang my repertoire then I started monologues

with my eyes closed I walked back and forth in the cell four steps forward four steps back

I invented dialogues for two characters that spoke different languages

like at the cinema when the film ends

there are those who make love who smoke there are those who merely exist

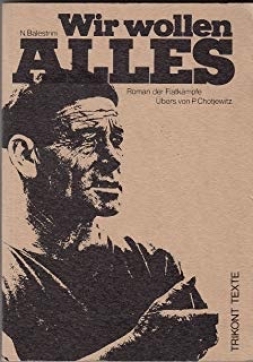

Nanni Balestrini, the radical Italian experimental visual artist, poet, and novelist known for recombinatory, revolutionary works that borrow from mass media, has died at age eighty-three. A key figure of the Italian literary Neoavanguardia (New Vanguard, or Gruppo 63) and part of the leftist Autonomia Operaia movement in the late 1960s and ’70s, Balestrini imparted the explosive politics of that era through collage and cutup processes focused on and made with collective language. His influential texts include the poetry book Blackout (1979), recently translated into English by Commune Editions, and his first novel Vogliamo tutto (We Want Everything, 1971), which was reissued by Verso in 2016. In addition to novels, poems, and collages, he also engaged in audiovisual work, as in Tristanoil (2012), a 2,400-hour video adaptation of his influential algorithmic novel Tristano (1966) first displayed in Documenta 13.

Born in Milan in 1935, Balestrini immersed himself in the city’s proletariat circles, becoming an editor and writer at numerous working class journals. In 1968, he cofounded Potere Operaio, a group committed to factory workers. Through his participation in avant-garde movements, like the Autonomia, that centered art in their activist interventions, Balestrini achieved national importance by dissolving public and private space in literature and visual art—categories that often bled together in Balestrini’s extensive oeuvre. In 1979, at the violent apogee of the internecine revolutions surging throughout Italy, Balestrini was arrested for alleged association with a leftist terrorist organization; unable to prove his membership, authorities released the artist, who fled to France, rumoredly by skiing down Mont Blanc. In his later years, he split his time between Rome and Paris. Balestrini’s art has been widely exhibited, including in the Forty-Fifth Venice Biennale; Balestrini gave a reading at the fourteenth edition of the Istanbul Biennial in 2015. A group exhibition at Laura Bulian Gallery in Milan titled “The Severed Language” includes Balestrini and is currently highlighted with an Artforum Critic’s Pick by Francesca Pola.

Asked by Rachel Kushner, in an interview for The Nation in 2016, how he feels about the unrest that he documented in his work decades ago, Balestrini said: “Everything is different; everything has changed. That period bequeaths us only an imperative: that we need to change the world, and that this is possible, necessary, and urgent—even if we don’t immediately manage to realize it as we’d like.”

ARTFORUM

I hear that Nanni Balestrini died last night

His book “The Unseen”, about prison and repression, militancy and the state, was an important book for me and my comrades in London. And then there was “We Want Everything”, about the revolutionary moment of 1969, a period which was inspirational to us. His writing is full of a fervour and realism that you see rarely in revolutionary literature. He wrote about violence, conflict, he had found a form that could match the activity of struggle – it wasn’t just that he set aside punctuation and embraced indirect speech; it was like a power of a storm pushing under calm waves. And it was clearly a product of that struggle, a work that bore witness to activity and in turn inspired it.

Last year, I finished translating The Golden Horde, the book he put together with Primo Moroni. It’s a volume that collected together writings from those movements building up to 1977, weaving them into a commentary, attempting an account of almost 20 years of political activity and generational turmoil, remaining honest to the flaws of those moments without betraying the revolutionary intentions. And when I finished, I went up to Rome to meet Nanni. And I was surprised – by this point I’d read his poetry, his other novels, I’d held more of that violent discourse in my head and hands – but when I met him there he was, the small, elderly poet and editor, Nanni with his clippings and wordsmithery, humble, quiet, happy to talk about those years of wonder. We sat in a small bar and talked for a few hours. He told me about how his father had owned a factory, and he took no interest in it – I noted the irony, for someone who would largely be remembered for writing about factories, for a book that literally includes a birds-eye view of a factory on its inside cover.

What you don’t immediately get from his more well-known works, from the period 1969–1979, is that he didn’t think of them as literature but as reportage – even if reportage filtered through the experience of the avantgarde, of that odd tendency of Neo-Kantian aesthetics that has been coincidentally prevalent in Italian communism. Three of the more well-known books are essentially other people’s narratives: “We Want Everything” is the account of the militant worker Alfonso Natella; “The Unseen” is Sergio Banchi’s memoir, told to Nanni when they were in exile in France together; “The Editor” is about Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, a close friend, who brought him into mainstream publishing.

He used to say that over that decade, there was no real literature in Italy, by which he meant nothing good. Just think about that for a moment – Umberto Eco (with whom he was friends), Italo Calvino (with whom he wasn’t), Elsa Morante (whose work he loathed)… He thought that for those ten years, everyone with anything to say did so by other means, by journalism or essays, militancy and organising. For him, the real work in those years was the editing – he was the editor, the curator, the typsetter, ordering the words, laying them on the page, newspaper after newspaper, not only Potere Operaio but many of its successors; he helped small publishers find the machinery necessary, tidied up their texts, brought them into a network, got the books out. Plenty of those books were literally pulped in the end, after the mass arrests.

He wrote a lot more after those years, good and fierce poems that not only try to reckon with a political past but also an artistic one, that deserve a place in our accounts of modernism. Here’s to Nanni – a modest man with violent words, a poet who tried – in his own way – to dedicate himself to the struggle for freedom.

Richard Brodie

Nous apprenons la mort de Nanni Balestrini. Nous ne le connaissions pas personnellement mais sans ses livres, “Nous voulons tout” et plus particulièrement “Les Invisibles”, lundimatin ne serait probablement pas exactement lundimatin. Le seul hommage valable à nos yeux c’est de vous inviter à lire ces livres.

LUNDIMATIN

MORT DE NANNI BALESTRINI, AGITATEUR INTELLECTUEL ET CULTUREL

Après avoir passé sa vie entre l’Italie et la France, le militant politique a disparu lundi à Rome. Il laisse derrière lui nombre de poèmes et œuvres artistiques engagés

Lundi s’est éteint à Rome Nanni Balestrini, poète, écrivain, essayiste, «agitateur culturel», militant politique. Une figure notable de la scène intellectuelle italienne et européenne, qui incarne à lui seul le «destin» de la génération qui «vint au monde» avec Mai 68, en vécut tous les espoirs et toutes les désillusions.

Au début des années 60, Nanni Balestrini, né à Milan le 2 juillet 1935, est déjà connu comme poète : il figure, avec entres autres Edoardo Sanguineti ou Antonio Porta, à l’avant-garde des Novissimi, et est reconnu comme l’initiateur et le «poumon» du Groupe 63, auquel appartiennent Umberto Eco, Alberto Arbasino, Furio Colombo ou Giorgio Manganelli. C’est un «alchimiste» qui, attiré par les expérimentations musicales de Berio ou Stockhausen, «mixe» toutes sortes de textes, d’images et de sons, mêle l’activité poétique aux arts visuels, au théâtre, à la musique, à la danse, à la peinture, à la bande dessinée, aux événements sociaux et, dans sa vie, se rend sensible à toutes les manifestations intellectuelles, artistiques ou politiques, de Radio Alice, soutenue par Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, à Alfabeta,la revue de critique littéraire qu’il fonde.

Après Mai 68, où il s’est engagé corps et âme avec ses camarades de Potere operaio (pouvoir ouvrier), il publie un «roman» – un «montage créatif» de documents bruts restitués sans syntaxe ni ponctuation – qui, traduit partout, lui donne une aura internationale: Nous voulons tout !, dont le titre même résume l’esprit de la revendication fondamentale, mais insaisissable et indécidable, de ceux qui voulaient «un autre monde».

Poursuivi après les «années de plomb» pour association subversive et constitution de bande armée, comme nombre de militants de Pouvoir ouvrier et d’Autonomie ouvrière, il se réfugie en France, où, notamment, il crée les éditions Manicle, expose ses œuvres picturales, réalise des performances, publie le premier numéro de la revue Change international. En 1984, reconnu non-coupable, il peut retourner en Italie, où il continue son œuvre d’infatigable «expérimentateur» de toutes les formes artistiques. En 1988, il publie avec Primo Moroni l’extraordinaire Horde d’or, document inclassable (montage de tracts, affiches, discours, chanson, films, théories…), traduit récemment en français aux Editions de l’Eclat, qui rend raison de l’histoire politique des années 1968-1977.

Robert Maggiori (Liberation)

On Nanni Balestrini, the Most Radically Formalist Poet of the Italian Scene

In the late 70s, Nanni Balestrini conceived the idea of a musical poem in collaboration with Demetrio Stratos, the singer of Area, whose exceptional voice was part of the Italian rebel movement’s sound. Then Demetrio died, while Balestrini was forced to exile in France. It was 1979, when the Italian State banned, arrested, and persecuted a group of intellectuals, workers, and activists known as Potere Operaio (Worker’s Power). The poet was one of them.

In fact, on the 7th of April, 1979, dozens of activists, workers, and writers were arrested under the false accusation of being the leaders of the Red Brigades, the militant organization responsible for the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, President of Democrazia Cristina, the nation’s governing party. Those activists, workers, and writers were actually guilty of a different crime: the crime of supporting the progressive movement of autonomia operaia.

That day was a watershed in the history of Italian society. In this country, “1968” had lasted for ten years. This is the historical peculiarity of Italy: the long-lasting wave of social struggle had countered capitalist aggression until 1977, and beyond. After nine years of continuous social conflict and cultural mobilization, the year 1977 was marked by a widespread insurrection of a sort, more Dadaist than Bolshevik, more poetic than violent.

In Bologna, Rome, Milan, and many other cities that year, thousands and thousands of students, artists, unemployed young people, and precarious workers staged a sort of ironic rebellion which ranged from carnivalesque parades to acts of semiotic sabotage to skirmishes with police to peaceful and not so peaceful occupations of entire quarters of cities.

After the ’77 insurrection of creativity, the Stalinists of the Red Brigades converged with the apparatus of the State in the attempt to annihilate the movement, and to enlist as many militants as possible in the project of military assault against the so called “heart of the State.” The convergence of State apparatus and red terrorism resulted in the isolation and in the final defeat of the movement.

If we want to understand the peculiarity of this enduring wave of social movements in Italy, reading the poems and the novels of Nanni Balestrini can be useful — even if Balestrini has never been a storyteller or a chronicler of neorealist descent.

Instead, Nanni Balestrini is simultaneously the most radically formalist poet of the Italian scene and the most explicitly engaged in a political sense. He follows a methodology of composition that may be named recombination, as he is always recombining fragments taken from the ongoing public discourse (newspapers, leaflets, advertising, street voices, politician’s speeches, scientific texts, and so on). But simultaneously he is remixing those fragments in a rhythmic wave that reverberates with passions and expectations and rage.

The peculiarity of the Italian movement of what would be called autonomia may be found in the concept of refusal of labor. Workers’ struggles were viewed from the point of view of their ability to destroy political control, but also and mainly from the point of view of their ability to advance knowledge and the technological replacement of human labor time in the process of production. The reduction of labor time has always been the main goal of the Italian autonomist workerist movement.

The words “operai e studenti uniti nella lotta” (workers and students united in the struggle) were not simply a rhetorical call for solidarity, but the expression of the consciousness that the workers were fighting against exploitation and students bore the force of science and technology: tools for the emancipation of time from the slavery of waged work.

In this social and political framework, literature was conceived as middle ground between labor and refusal of labor. Literature may be viewed as labor, according to the structuralist vision purported by the French formalists of Tel Quel, but literature may also be viewed as an attempt to emancipate the rhythm of language from the work of signification. Poetic language is suspended between these two attractors.

This double dimension is the defining feature of Balestrini’s poetics: formalism of the machine, and dynamism of the movement. Cold recombination of linguistic fragments, and hot emotionality of the rhythm. Although the event is hot, this poetical treatment transforms it into a verbal crystal, and the combination of verbal crystals gives way to the energy of a sort of a-pathetic emotion.

Since the sixties, Italian culture had been traversed by the cold fire of a certain kind of sperimentalismo that was named Neoavanguardia, in order to distinguish that movement from the historical avant-garde that in the first decade of the century burnt with a passional fire, aggressive and destructive. Italian sperimentalismo was inspired by Husserl’s phenomenology and the French nouveau roman; it was influenced as well by Frankfurt School critical theory, and by the colors of Maoism spreading everywhere in those years.

Umberto Eco, Edoardo Sanguinetti, Alberto Arbasino, and many others were involved in Neoavanguardia, whose style was based on the elegant game of quotations, winking and hinting. Then, from its cold fire emerged the angelical and diabolical face of Nanni Balestrini, cool head and warm heart. Or, contrarily, cool heart and hot head, who knows.

Anyway, Balestrini managed to keep a cold experimental style while dealing with very hot subjects and verbal objects. Angelic cool of the recombinant style, and diabolical hotness of the events, of the characters, of the gestures. Violence is often onstage in his writings. The well-intentioned violence of the autonomous of Fiat workers in Vogliamo tutto (We Want Everything); the livid violence of the precarious, marginalized, and unemployed in La violenza illustrata; and the mad violence without historical or social explanation in I furiosi and Sandokan. In those novels violence is recounted without sentimentality and without identification. No condemnation, no celebration, a purely rhythmic interpretation of good and evil, of the progressive and of the aggressive forces that explode in the streets, in the factories, in the campuses, and in daily life.

According to a widespread common place, the 70s are recorded as the decade of violence. Yes, since 1975 many people have been killed on both fronts of the battle, when a bill passed by the Parliament allowed policemen to shoot and kill if they felt in danger. All through the years 1969-76, activists and students were killed by fascists and cops. At a certain point they decided to react, to build molotov cocktails and take up the gun. As a consequence, cops and fascists and some politicians and corporate persons were attacked, some killed.

It must be said that in those years violence was highly ritualized and charged with symbolic meaning. Nevertheless, in the following decades, and particularly in the recent years of this new century, violence is far more pervasive than it was in the seventies. It is less emphasized, less advertised, less ritualized, but it percolates in the daily behaviour, in labor relations, in the rising tide of feminicide and child abuse, and in the wave of political hatred that never becomes open protest, never deploys as a movement, but flows through the folds of public discourse.

Balestrini was literary witness in the theatre of social conflict, but simultaneously he was an actor on the stage. Nevertheless he has managed to be ironic and distant, while being involved body and soul. This is why his literary gaze is both complicit and detached. His poetics have nothing to do with the psychological introspection, or dramatic expressiveness. His work consists in combining words and freezing actions into dance. The narration strips events of their passional content, pure gesturing devoid of content. But the dance turns into breathing and breathing turns into rhythm, and emotion comes back from the side of language.

Balestrini is not uttering words that come out from his soul (does Balestrini have a soul?). Words are but verbal objects proceeding from the outside world. Voices are broken, fragmented, assembled in sequences whose rhythm is sometimes gentle, aristocratic, and ironic; sometimes furious, violent, and crazy. The act of the poet does not consist in finding words, but in combining their sound, their meaning and their emotional effect.

Since the 60s Balestrini started writing poetry for computer, and his declared intention was already in those years to make poetry as an art of recombination, not an art of expression. The computing poet combines verbal detritus and musical waste grabbed at the flowing surface of the immense river of social communication. He assembles decontextualised fragments that gain their meaning and their energy from the explosive force of the combination (contact, mixture, collage, cut-up).

Following this poetic methodology Balestrini has traversed five decades of the Italian history, transforming events and thoughts into a sort of opera aperta (work that stays always open to new interpretations). He has shaped furies and utopias, euphorias and tragedies that have marked the history of the country.

Franco Bifo Berardi (LITERARY HUB)

‘I Am Interested in Collective Characters’: An Interview With Nanni Balestrini

I’ve been an admirer of Nanni Balestrini for many years, ever since I first read The Unseen, a funny, strange, and devastating novel about Italy’s Movement of 1977. His 1971 novel, We Want Everything, has just been translated into English. In September, I finally met Balestrini—or, rather, he met me: He’d taken a taxi all the way to Fiumicino Airport, on the outskirts of Rome, to await my arrival. We made our way into the city and had lunch. Balestrini is 81 but looks about 60, and he’s more of a refined dandy and perfect gentleman than any anarcho-communist I’ve ever met. When I excitedly launched into a series of questions about his life in the movement, he said, “This is lunch, not a biographical study,” and worried about what kind of wine to order. Everything in its place.

RK: I wanted to ask how you built the voice that appears in We Want Everything. I know The Unseen, for instance, is largely Sergio Bianchi’s story.

NB: We Want Everything is the story of a real person, Alfonso; he told me everything that’s in the book. He is a collective character, in the sense that in those years, thousands of people like him experienced the same things and had the same ideas and the same behaviors. It’s for this reason that he has no name in the book. I am interested in collective characters like the protagonist in The Unseen. I think that unlike what happens in the bourgeois novel—which is based on the individual and his personal struggle within a society—the collective character struggles politically, together with others like him, in order to transform society. Thus his own story becomes an epic story.

RK: With Alfonso, you seem to have hit the jackpot in terms of these thousands that you talk about who migrated from the South, went to Fiat, worked, revolted… he’s incredibly funny and insightful. Can you recount a bit about how you met him?

NB: You’re trying to get me to give Alfonso his individuality back, to break him out of his collective figure. I really can’t respond to questions like that.

RK: I’m assuming you were attending meetings, protesting outside the factory gates, talking to workers, inquiring about their conditions and lives?

NB: As is the case with a lot of the comrades who participated in the 1970s movement, the great workers’ struggles were at the center of our activism. That is how I knew about the Fiat struggle that’s talked about in the book—I followed it at close quarters; I lived it together with the protagonists. It was something that I saw and experienced.

RK: Today, particularly in the United States, there is a growing interest in the women’s movement that was starting to take form just after the “Hot Autumn” of 1969, and in particular much talk about Lotta Femminista and Maria Dalla Costa’s The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. Looking back from this vantage point, would you have anticipated that the ideas emerging from Italian feminism would be such a lasting achievement from that era? Perhaps because the factory is essentially gone, but the family remains, for better or worse.

NB: The factory has not disappeared; it has just lost its centrality to society by way of automation. For feminism, as for communism, the stages through which the bases of great social transformations are realized cannot be moved through rapidly. That’s always a vain hope. It takes long periods—generations, if not centuries. But it is important that there is a tendency that way which is maintained despite the halts, reverses, and backward steps.

RK: You were a fugitive, then an exile. Now you again live in Italy. Autonomia, an era that you documented so critically, has seen a resurgence of interest among leftists. Do you tend to think much of the past?

NB: I consider myself lucky to have been through an extraordinary and happy period. It would be senseless to search that period for something that could be applied politically in a radically different situation like the one we’re living in 40 years later. Everything is different; everything has changed. That period bequeaths us only an imperative: that we need to change the world, and that this is possible, necessary, and urgent—even if we don’t immediately manage to realize it as we’d like.

Rachel Kushner (THE NATION)

Nanni Balestrini and the Poetry of the Italian Autonomia

Today’s ongoing debate about the relationship between art and activism is one that too often seems to arrive at a dead end. These two grand abstractions – too grand, too abstract perhaps? – seem to repel one another with an almost magnetic indignation. The possibility of fusion is frustrated by difficult questions, the reductiveness of political language, the vulgarity of propaganda, the sheer ugliness of naked ideology.

Few can claim to have confronted and surpassed this dilemma more effectively than the writer and artist Nanni Balestrini whose poetic craft has, for decades, been intimately embedded in the realities of Italian social movements. His art was born from a particular set of struggles that emerged in the 1960s and 70s, most notably the wave of protests and occupations that would lead to the formation of Autonomia Operaia, a leftist movement which challenged the Communist glorification of work. This disparate group, too often reduced to its concluding apocalyptic violence, has been largely abandoned as a strategic political model. But it is in the artistic sphere, and in Balestrini’s poetic work in particular, that the imaginative legacy of this generation lives on in its most vivid and urgent manifestation.

One of the most important examples of this, and the most interesting for both artists and activists today, is Blackout, first published in 1979 and, as of this week, now finally available in English translation thanks to Commune Editions. The text is a perfect example of how literature can expand outside of its usual social boundaries: the private space, the isolated ‘intellect.’ The poem – split in four ‘chapters’ – tells the story of the movement’s birth to its final moments, the dark days in which the ‘lights’ went out. It is a pastiche of the epic, a meditation on the collapse of movements, the loss of hope, community and love.

Blackout is structured through a series of repetitive leitmotifs, composed by the poetic organization of cut up fragments from books, magazines, other poems, transcriptions of radio broadcasts, protest slogans, government reports, even tourist guidebooks. These are then (re)assembled in an ‘intertextual’ collage. This extract from the second verse of the first section is typical of the style:

for days a poster illuminated the walls of Milan

dark clouds swollen with rain transitory showers that lasted the evening then two rainbows

a river of blue jeans

in heaven at last a glimmer of light there will be no flood

a segment of Milan is deadlocked

Each phrase asks the reader to speculate as to its origins, each contains its own individual energy or aura. ‘A segment of Milan is deadlocked’, for example, reeks of journalistic detachment, made all the more obvious by its strange amputation here. Meanwhile, the poster which ‘illuminated’ the walls of Milan has a romanticism, youthful and futuristic. Then there is the ‘glimmer of light,’ in heaven, opposed, of course, to the blackout of the poem’s title. ‘Could this be from the Gospels?’ asks the reader.

At the same time the fragments also have a collective identity by virtue of their position in the verse. Sticking with these first two examples, the difference in tense – past to present – serves to reinforce the distance between the newspaper cutting and presumed activist pamphlet. So too does the physical space between them (not to mention the conflicting rhythms). From this example alone we can see that each poem, collectively, has its own identity, established by the act of remixing. Later, several fragments return in new contexts, entering into new textual relationships:

a river of blue jeans

a carpet that smothers the bleachers and descends to completely hide the lawn

thousands hundreds of thousands of voices for communicating

a carpet of shoulders of heads and arms that seem like agitated waves under gusts of wind

for days a poster illuminated the walls of Milan

There’s that ‘river of blue jeans’ again, but this time it’s attached to the physical images of a crowd, surrounded by ‘shoulders of heads and arms’ and ‘hundreds of thousands of voices.’ It is a powerful, audio-visual device. The images of protesters seem tangiable, animated, emerging from darkness as if through a cloud of smoke or tear gas which characterised those demonstrations. Repetition here is used to draw attention to the synchronicity of experience – the multiplication of demonstrations – almost like the clarinets of Steve Reich’s New York Counterpoint jutting in and out of one another.

This formal device is central to understanding the poem’s political message. Balestrini, in form and here in content, is signifying historical memory, the resistance of the movement to its own silencing by the state, by repression. His biographical experience – he himself was accused of supporting terrorism and later found innocent – is entwined entirely with the larger social dynamic. This becomes more explicit as the poem moves forwards and the fragments begin to unite around concrete depictions of struggles:

feminists sneer every time a male gives orders

it is the world of use-value that conflicts with the factory and production

above all the manager feels their contempt on his skin

Fiat fears their hatred of the factory

there are gays that make faces they write Long Live Renato Zero on the walls

by 1979 even hope is exhausted the factory is no longer the place where the fight for power is waged

study travel play become an artist or go to India

they are not thinking about the day they will leave Fiat

Many of these themes resonate with today’s ‘European crisis.’ We read about feminism, homophobia, post-industrial economics, about young people who “come from another planet”, cities “disrupted by immigrants dehumanized in the ghettos where the quality of life is tragic.” But it is the collection and collision of these issues, approached from different angles, spoken in different dialects, that is most significant. Balestrini himself seems virtually absent, present only the space between lines, in the silences. The voices of the poem are subsequently able to develop a kind of autonomy, a chorus constantly shifting in rhythm, intonation and emotion.

We experience rage:

after a few minutes the night was illuminated by fires the streets invaded by looters

Melancholy:

there are those who make love who smoke there are those who merely exist

Humour:

the Fiat bosses have never seen the workers laugh and it is an outrage to our Lady

Fear:

with regard to articles 252 253 254 of the penal code we order the arrest of

Boredom:

the reentry of the 85-ton cylinder is now expected by

And so on. Balestrini’s organisation of these fragments engenders a poetics that is polyphonic, multi-vocal, and embedded in a specific time and place. The cold factory instructions for example, the ’85 ton cylinder,’ obtain a new meaning in the poem, become connected with mass media, with the language of crowds and, ultimately, with the movement itself. This is collective narration, where the job of the poet is to assemble voices rather than express a single, mysterious, idea.

The result is a duality. The intense attention to structure, the formal regularity combines with the rhythms of speech, of popular discourse in a synthesis, a kind of dance in which movement and grace precludes the idea of closed Hegelian resolution. As the philosopher Bifo Berardi, also a one-time participant in autonomist groups, puts it in his introduction: “This double dimension is the defining feature of Balestrini’s poetics: formalism of the machine, and dynamism of the movement. Cold recombination of linguistic fragments, and hot emotionality of rhythm [emphasis my own].”

This is particularly evident in the later verses in the series, which describe a figure alone in a prison cell, symbolising the collapse of the movement’s dreams. Blackout ceases to be connected to action, industrial sabotage, and mutates into its more common meaning, “a momentary loss of consciousness or vision.”

I was afraid when the snow came into the cell

like at the cinema when the film ends

white threads stirred at the window’s double bars and drifted through the openings

guards on the night shift shouted at me to remove the cover from the window

it was like looking through a milky glass sheet

The cut-up public discourse – the image of the cinema, an audience – is deployed to divert ‘spectacle’, forging a remarkable empathy with the unnamed protagonist who the reader has only just encountered. The emotional rhythm appears intimate precisely because of the ambiguity and inherent distance of the source materials.

So while the cold logic of Balestrini’s assembly line is still there – the rigidity of prison bars, welding machines, the confines of the sonnet and villanelle – here it is used not to depersonalize but quite the opposite, to give flesh and bone to the figure described. Their punishment, like that of the poet’s friends, is negated through a language that transcends rigid boundaries, violating the rigid divisions between ‘inside’ and ‘outside,’ enacting, in other words, a prison-break.

Conclusion

Balestrini’s particular techniques of appropriation, assemblage, and rhythmic assault are a unique intervention in poetry, a radical evolution of the avant-garde cut-ups pioneered by earlier artists like Jean Arp and Vladimir Mayakovsky. But while Surrealism, Dada, Zaum all sought psychological liberation, Balestrini, inspired by the politics of autonomia, calls for a renegotiation of the binary between individual and collective, in which society itself is reconstituted by poetic logic.

What would such an experiment look like today? Perhaps a 21st Century response to Blackout would recompose Internet fragments, juxtaposing election manifestos, tweets, scientific surveys and blog posts. Or perhaps it would intervene against finance, jamming stock market argot with the slogans of occupiers, the rhythms of graffiti.

At the core of Balestrini’s poem is the idea that while machines have revolutionized society, their alienating power must be reclaimed by the artistic energies of social movements: a multitude. In a recent Talk Real interview Maria Hlavajova spoke about art’s capacity to “add affects” to “concepts we need, like democracy and equality.” The idea is a neat one, but too one-directional. What Balestrini’s poetry proposes is almost the opposite, a poetics in which concepts like democracy and justice evaporate altogether, hollowed out by history. While the consequences of this are dire, violent, he suggests there is a unique opportunity to build something new, something eternally suspicious of abstraction. A true humanism, perhaps.

The translation of Blackout is a quiet event and one that will be destined, for now at least, to remain in the corners of both the activist and literary worlds, so separate, so seemingly irreconcilable. Today’s social movements, lacking in institutional power, are far from the point of canon-building. Nonetheless, for both its historical ambition and formal inventiveness Balestrini’s work remains a vital resource for individual artists seeking to escape the paralysed aesthetics of the contemporary art world.

JAMIE MACKEY (POLITICALCRITIQUE)

what the fuck do I care about the Law

a fifty-year-old woman with a shopping bag enters a store saying today

she shops for freethe shelves of the new supermarket Fedco glistened white and empty

while a mush of various foods stained the floorswhen I left the area was on fire and the flames seized the small amount

the looters had left behindjets of black water from the broken hydrants swept away what remained

of the plunder to the center of the streetwe’re going to take what we want and what we want is what we need