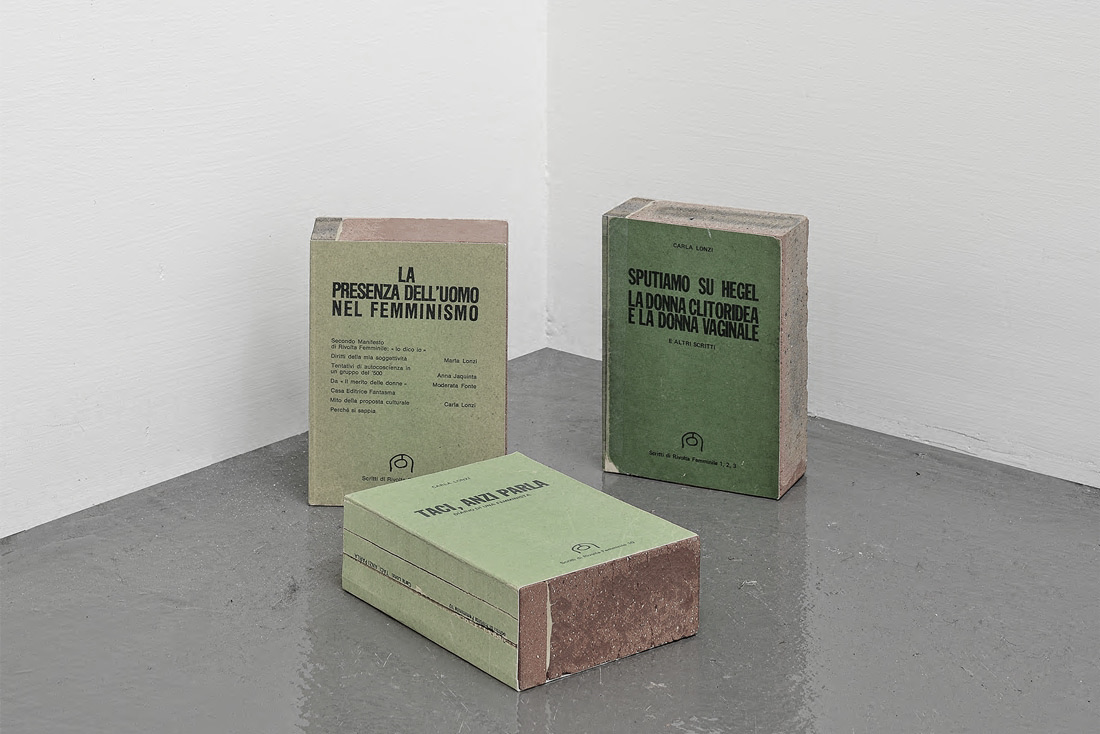

In 1969, the Italian art critic and feminist Carla Lonzi (1931-1982) authored Autoritratto (Self-Portrait) using the transcripts of interviews conducted with fourteen prominent artists living in Italy: Carla Accardi, Getulio Alviani, Enrico Castellani, Pietro Consagra, Luciano Fabro, Lucio Fontana, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Nigro, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, Mimmo Rotella, Salvatore Scarpitta, Giulio Turcato and Cy Twombly. Overlooked for many years, Autoritratto’sexperimental unravelling of traditional art criticism has garnered increasing attention since its republication by Et al./Edizioni in 2010. It was, however, Lonzi’s final work as an art critic; after its publication she renounced the art world, co-founded the collective Rivolta femminileand wrote a number of feminist texts including Sputiamo su Hegel (Let’s Spit on Hegel), La donna clitoridea e la donna vaginale (The Clitorial Woman and the Vaginal Woman) and Taci, anzi parla: Diario di una femminista (Shut up, or rather, speak: Diary of a Feminist), among others.

Teresa Kittler So many people came under the spell of Carla Lonzi.

Allison Grimaldi Donahue There are so many people involved in the translation now that it feels meant to be. Especially all the people who aren’t Italian but really care about Lonzi’s work and want it to be in English. It’s part of the mythology of Carla Lonzi, the feminist icon. But also I think the fact that she ended up abandoning art, for art’s sake, speaks to a lot of people today.

TK In some ways, Autoritratto is a strange book. It’s a series of interviews that Lonzi recorded throughout the 60s and then collated, ostensibly by transcribing them word-for-word but in truth she messes around with the order and does a lot of cutting and pasting… it’s an ambitious book, and was certainly unique at the time. How the hell do you start translating it?

AGD I’m continually learning. Lonzi’s process was to transcribe every word that the artists said, whether it’s a bo, meh, or uh, as well as their non-sequiturs, repetitions, and circular conversations. That’s been a challenge because I want to respect her process, but I also think that, as a translator, you want the text to be legible while keeping it true to its meaning in the original language.

TK In the extract of your translation on the Los Angeles Review of Books, Lonzi talks about the alchemical process, the magic, of transforming spoken language into written words. How do you think the act of translation compares to that transformation?

AGD I’m not sure that there is a difference between writing and translation. All the material I use to write is already in the world. Language exists in the world without me. Written language isn’t usually tied to spoken language in an immediate way in normal life. But in Autoritratto they overlap because she transcribed every word the artist’s spoke. It’s a spoken text – highly oral and highly textual, with all the artificial elements of any written text because she rearranged the words to make her own argument.

TK There’s an anecdote where one of the artists Lonzi interviewed, Giulio Turcato, reads Autoritratto and tells Lonzi that he doesn’t recognize himself. On the one hand, Lonzi restrains from mediating in an effort to redefine what the art critic ought to be. Autoritratto is part of a bigger moment in the 60s where the myth of the unmediated or the ‘raw’ experience gains prominence. At the same time, however, what she’s doing is so highly artificial and has really literary ambitions. It’s interesting to discuss her with a writer because she’s usually referred to solely in an art historical context. Tell me, do you rate Autoritratto as a literary text?

AGD I approach Autoritratto as a text. I’m interested in all the ways we can write about art. When I was a graduate student, Trinie Dalton introduced me to thinking about how art writing is a form of art in itself. I think of Lonzi as the foremother of writers like Lynne Tillman and Moyra Davey who take art criticism and do something completely their own with it. Autoritratto is the urtext of so many things, but it’s been forgotten. So many contemporary writers want to do what Lonzi did in 1969 but have no idea of her as a precedent. Lonzi was working at the same time as Sontag but, unlike Sontag (who made a clear division between the artist and the critic), she announces herself as a critic in a way which feels like it’s her first move as an artist.

TK Although Lonzi does talk about criticism as a creative project, her friends tend to put it down.

AGD The form of Autoritratto basically explains her arguments, but also in The Solitude of the Critic she says the same thing. Lonzi’s concern was that the critic had become dissociated from art itself when in reality you are part of art, you are an artist.

TK I find it poignant that she’d thought of herself as working or contributing as an artist, or within a certain milieu, and then realized that she wasn’t being understood on her own terms.

AGD It’s awful that she had to break with the art world and that she didn’t feel understood by the people closest to her. There is one thing I haven’t figured out, and I wonder if you have… what did leaving the art world mean to her? And did it have something to do with questions of scarcity, in a way? Carla Accardi is the only female artist interviewed in Autoritratto, aside from Lonzi herself, was there not enough room for two female artists?

TK . It’s interesting to look at MAMbo’s exhibition of Autoritratti, which looks at Lonzi’s legacy among female artists and remember that Lonzi herself refused the possibility that there could be a legitimate feminism that went hand-in-hand with art. At the root of her split with Accardi, there’s the question of whether there could be a genuinely liberated, legitimate feminist artist. There are some art historians trying to think about why it could be that Lonzi holds onto positions that had already been challenged. This idea that it is impossible for a feminist project and an artistic project to coexist, or when she talks about the fact that as a woman she could only ever be seen as an ideal spectator… the art world was confronting these ideas in the 60s. In a way, Lonzi holds onto certain ideas of what art is, and the role of the artist-as-ultimate-protagonist, which were outdated at the time.

AGD I think today there can be a feminist artist. I think today, yes, it’s very possible. It would have to be. I would be a terrible pessimist to think otherwise. But back then? That decision doesn’t seem crazy. But, for Lonzi, women have to be in power and decide the future. Women haven’t had their time, their chance, so why should they be after equality?

TK Yes, and there were other artists too who ended up making the same decision.

AGD And in a way, she didn’t leave it.

TK That’s true, she left the art world to write about it. And a tradition of art writing based in biographical writing has definitely flourished in her wake. Does Autoritratto remind you of a particular writer or tradition? In some ways, it looks like an autobiographical novel, with all the images included.

AGD Because it contains many voices, it reminds me of many different things. It reminds me of Jill Johnston, and she does say a lot of the same things Sontag says about criticism. But a lot of it is pretty unique. There’s one moment her toddler comes in, and he’s screaming about art too. Her criticism is interesting but it’s not that different from other works of criticism coming out of Italy in the 60s – it’s the fact that she leaves in her young child’s interruptions which makes it completely new. When Lonzi looks at a work of art, she has all the academic knowledge, but she is also interested in the physical experience of looking. She says, “I’m here and I have a body.” I think of Lonzi as a lyrical essayist.

TK I sometimes imagine how Autoritratto came about. The moment she decided to start collating these reams of interviews. I think of how the life of the translator might look – at her desk with her recorder. Even just thinking about the work it would take to piece these things together makes me wonder what that process looked like. There’s this growing intimacy that must come from listening over and over to someone via a recorded interview.

AGD But because it’s an intimacy built from hours and hours of recording, it’s really one-sided.

TK Do you get a sense of what kind of interviewer she is? To what extent she’s partial or impartial?

AGD Oh, she’s partial. The act of making this book is partial. I think her behaviour does change depending on who she’s interviewing – the tone has a lot to do with hierarchy and age. It’s playful and fun with Scarpitta while with Consagra there’s more headbutting. You can tell she spent a lot of time with some of the artists. With Consagra, they immediately start talking about feminism and psychology and sublimation, about how the artist is the only man who’ll look at his own shit. Lonzi calls him an idiot. She says, “who do you think gives birth?”; she’s aggressive, she puts them in their place. A lot of the men have theories. They think they have a vision. They think they have a gift. They quote De Chirico’s line about how his hand has a magic power when he paints and they relate that to themselves.

TK They’re still holding onto mythologies.

AGD They think of the artist as a different kind of person to a regular person.

TK I come across it again and again. Even Alighiero Boetti cultivated that image of himself as having some kind of special insight, you know, very much in that hermetic tradition of the artist.

AGD And I guess, yes, perhaps if you spend all your time on your own working with materials or with language you do have insights. Of course you do. But they’re not insights that aren’t available to anyone else through any other means. I think it’s Castellani, who says he is more spiritual than the average man because he is closer to the average man… that he’s so human he’s more than human… It doesn’t make any sense, when you parse it apart.

TK Did the interviews change your opinions on any of the artists?

AGD I think that listening to all these artists in such detail and spending time with each of them really shows you the multiple faces, I guess the multiplicity, of the past and of the artists of this period. It is easy to be angry. I am angry. I’m an angry feminist. It’s easy to be angry with the past but spending so much time with each of their voices, you see them as whole people and you see that they contradict themselves and, because they are relatively young here, you see them trying to work through questions just like we are. In 1963, they’re trying to solve the problems of criticism. They’re dealing with the need for a new kind of interaction between the public and art. In the Italian context, I think this need to change is still felt.

TK To me, that Autoritratto presents all these different perspectives is one of its literary achievements. It is a form that has its own tradition (which is the thread of the humanist text) – the idea of the interview as an opportunity to show multiple perspectives on a subject.

AGD Even in the Greek text, it goes back to the symposium.

TK Exactly. And it’s a real tribute to Lonzi that she can do this with a one-on-one dialogue.

AGD It’s almost a novel. You see the conversations develop and grow over time. Points of view change. It takes something and turns it into something else, taking one sort of text and turning it into another kind of text. In the end it’s about art and it’s about feminism and it’s about all these people but, most of all, it’s about Lonzi. She points directly at it with her title.

TK The title, Autoritratto, it makes you ask whose portrait it is. What do you think of the photographs Lonzi included in the book?

AGD It’s like a slant rhyme. It’s not like Luciano Fontana is talking so we see a picture of Fontana, no, we’ll see a picture of Fontana’s mother as a child. You wonder, what does this image have to do with what they’re talking about? It’s her association. I love the images because they’re Sebaldian.

TK It’s a nice way to think of them, as associative images.

AGD It’s also a family album. There are snapshots of herself and her child too.

TK And also, we don’t know whether she invited the artists to submit photographs or images of their choosing. It’s another thing we just don’t know about her process. The book itself is seemingly such a straightforward idea of transcribing an interview word-for-word, but it arrives at something that so exceeds the possibilities or expectations of that apparent process. She turns an interview into something that has a kind of arc into literature. There’s something prosaic about the images included in the book but at the same time it opens up a world for us.

AGD It has a scrapbook quality that makes it both more familial and an art project. It does two contradictory things in our mind. We can accept that now, but to the artists at the time it might not have been understandable. It exceeds, right, it endlessly creates meaning and the images add to that. I love how the images break up the book, how they make you think of something else, and how they remind you that they’re talking about art, about visual art. Lonzi’s like, “Don’t forget to look at the work. Don’t just talk about the work, look at the work.” Which people don’t do enough.

TK What have been the challenges of translating this book?

AGD I have the impression (Carla would hate me for this) that she edits herself more than the other artists. She keeps all of their mistakes but is herself very articulate on complex ideas about women in art, the history of art, the development of criticism, in ways that take me a long time to understand. They are often the kind of sentences you have to float over and sit with for a while.

TK You think they’re too polished?

AGD They’re very literary.

TK You think they’re too rehearsed?

AGD Maybe some of her questions were written down but perhaps she’s so articulate because these are subjects she’s been thinking about for some time.

TK [laughs] So she’s given herself an unfair advantage.

AGD [laughs] Obviously, it’s her book so there’s no doubt about that.

TK Ok, so perhaps they’re rehearsed so they come out in a polished way but if she is editing herself so that she comes across as more erudite or articulate or as having more provocative or challenging thoughts then it speaks of a kind of insecurity.

AGD Or maybe she’s just treating their voices as a piece of found material. She’s the manipulator, she is the fabbro… they sold their voices away.

TK There’s a photograph taken by Giulio Paolini’s partner Anna of Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi, Luciano Fabrio, Luciano Pistoi and Giulio Paolini at Alba. They’re all asked to strike a pose to represent what they’re doing artistically. Accardi assumes the pose of a tent, the gallerist Pistoi positions one of the artists and Lonzi’s hands assume the shape of a book. She’s reading. Lonzi’s métier is the artists but is also the text. Do you think she’s reflecting on, or mediating, what it means to write?

AGD I don’t know if I would say she’s reflecting on writing in particular, perhaps more on what it means to work. I don’t know if she would have thought about it that way.

TK Have you come across any passages in Italian whose meaning you’ve felt is lost in translation and how have you dealt with that? Have you thought, “What will this mean in English?”

AGD The question of what it’s going to mean in a different language is very difficult. Even the current Italian edition doesn’t tell you who the artists and interviewees are. I don’t think a very well-educated Italian public will necessarily know everyone mentioned in the text, even if the reader is someone interested in art history. There are a lot of minor figures and no footnotes. The book is deeply Italian, and it transcribes a particular way of speaking that I really want to communicate in English. Italian has a much more flexible structure, so you can have sentences that ramble and list a bit without having a verb or a subject whereas in English we just don’t do that. You might sound a bit funny if you did it, but it’s not something that you do. In Italian, it’s a specific intellectual mode of communication where you can philosophize and ramble… as I’m doing now. It’s a style that the men in Autoritratto all adopt: they repeat themselves, they do long loops of phrases, which is hard to translate into English without making them sound stupid. I hope it opens up questions for English readers about the nuances of European feminism – Italian feminism is a very particular thing and there’s a lot there to research, but first you have to orient yourself within the loop de loop of Italian.

TK It’s a book that’s achieved an iconic status now among scholars and people studying Italian post-war art, but also scholars interested in the history of Italian feminisms. Why do you think it’s so important and how do we make sense of the fact that a generation of feminist artists are interested in her work, even though she believed that it was impossible to be a feminist and an artist?

AGD A lot of my friends who don’t read Italian are really enthused by the project. I think when you’ve heard about this text that’s been important for so many people but you can’t access it, you really want it to exist in your language.

TK I suppose there have also been so many critics and curators who have said that they are following in the footsteps of Lonzi. It’s not just a myth, it’s her and the work she’s done and the originality and the singularity of what she did and has done, but it is also the kind of repeated reference of her name.

AGD Of course she’s a figure, and that makes me nervous because I want to do her justice so that her myth continues but is more grounded. Carla Lonzi was one of the critics and she deserves her place amongst those people. Being in English gives her a whole new life. It’s a huge responsibility.

TK Going back to that tension that we touched on earlier…

AGD That’s the thing, I know that people will disagree but I think people latch onto her because she left the art world. I think a lot of us are frustrated with the art world, with the world that’s been handed to us, but we can’t help but make work – whether that’s as an artist or a scholar or a writer. Lonzi knows that it’s a vocation, so even though she renounced art she kept going and made a space for other people to keep pushing.

TK That’s quite moving, that she made space.

AGD I think she did that. Lonzi expands the notion of what a practice is by having her teach-ins and all these writings… other people did similar things and called themselves artists, but Lonzi called herself a radical feminist.

The work of Allison Grimaldi Donahue (b. Middletown, Conn.) has appeared in Electric Literature, The Brooklyn Rail, Words Without Borders, Flash Art, The Literary Review, BOMB, Tripwire, The Massachusetts Review, Prairie Schooner, and other places. Her book of poetry Body to Mineral was published by Publication Studio Vancouver (2016). She is also co-author of On Endings on Maurice Blanchot with Delere Press (2019). She has given readings and performances of her work at HyperMaremma in Tuscany and Gavin Brown Rome. She is Associate Translation Editor at Anomaly and collaborated as editor of fiction and special issues for many years with Queen Mob’s Teahouse. She has been a fellow at Bread Loaf, the Vermont Studio Center and the New York State Writers’ Institute, as well as artist-in-residence at Mass MoCA. She holds an MA in Italian Literature from Middlebury College and an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She teaches creative writing at John Cabot University in Rome and is currently an artist in residence at MAMbo, the Museum of Modern Art Bologna. Her translation of Autoritratto, Self-portrait is forthcoming in autumn 2021 from Divided Publishing.

Teresa Kittler is a lecturer in Modern and Contemporary art. Her research focuses on artistic practices from 1945 to present day, with a special interest in Italian postwar art, primarily on issues related to art and the environment and feminism. Since completing her PhD, she has been the recipient of fellowships from the British Academy/Leverhulme, the British School at Rome and the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA), and is the 2020-2021 Scholar in Residence at Magazzino Italian Art. She has also worked as Assistant Curator for the 10 Gwangju Biennale (2014). Teresa is currently working on a book project, titled Habitats: Art and the Environment Italy, 1945–1975, which examines artistic practice in Italy in the three decades following the Second World War, through the lens of habitat.

Links:

An extract from Carla Lonzi’s Self-Portrait, translated by Allison Grimaldi Donahue, which will be published by Divided Publishing in 2021.

Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi, edited by Francesco Ventrella and Giovanna

Carla Lonzi | Let’s Spit on Hegel