TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Charleville, August 25, 1870

Monsieur,

How lucky you are to be out of Charleville! In all the world, no more moronic, provincial little town exists than my own. I have no illusions about this any more. Because it is next to Mézières—which no one has heard of—because two or three hundred infantrymen wander its streets, my sanctimonious fellow residents gesticulate like Prudhommesque swordsmen, not at all like those under siege in Metz and Strasbourg! How dreadful, retired grocers donning their uniforms! How marvelous, as though that’s all it takes, notaries, glaziers, tax inspectors, woodworkers, and all the well-fed bellies, which, rifles held to their hearts, make their shivering show of patriotism at the gates of Mézières; my countrymen unite! I prefer them seated; keep it in your pants, I say.

I’m disoriented, sick, angry, dumb, shocked; I was looking forward to sunbaths, endless walks, rest, travel, adventure, bohemianism, but: I was most looking forward to newspapers, books . . . —Nothing! Nothing! The mail brings nothing new to bookstores; Paris is having a fine time at our expense: not one new book! It’s like death! I’ve been reduced to reading the estimable Courrier des Ardennes, owned, run, directed, edited-in-chief and edited-at-all by A. Pouillard! This newspaper sums up the hopes, dreams, and opinions of the local population; see for yourself! —I’ve been exiled inside my own country!!!!

Happily, I have your room: —You do recall that you gave me your permission. —I’ve borrowed half your books! I took Le Diable à Paris. And is there anything more ridiculous than Grandville’s drawings? I took Costal l’indien, and La Robe de Nessus, two interesting novels. What else? I read all your books, all; three days ago, I sank as low as Les Epreuves, and then to Les Glaneuses— yes, I went so far as to reread it—but that was it. Nothing more; I’ve exhausted my lifeline, your library. I found Don Quixote; yesterday, I spent two hours looking at Doré’s woodcuts; now I have nothing! I’m sending you some poetry; read it one morning. In the sun, as I wrote it: I hope you aren’t a teacher anymore!

It seemed to me that you had wanted to know more of Louisa Siefert when I lent you her most recent poems; I just managed to find some pieces from her first book, Les Rayons perdus, 4th edition. In it I found a very moving and beautiful poem, “Marguerite”:

Off to one side, bouncing on my thighs

Was my little cousin with big sweet eyes.

Marguerite is a ravishing girl,

Blonde hair, little lips like pearls

And transparent skin . . .

Marguerite is too young. Were she mine . . .

Had I a child so sweet, blonde and fine . . .

A delicate creature in whom I could be reborn

Pink and guileless with a stare so forlorn

That tears rise to the rims of my eyes

When I think of her bouncing on my thighs.

Never to be mine—an absence I mourn

Because fate, heaping me with scorn,

Delights to see love devoured by flies.

No one will say of me: ah, such a good mother!

No child will look at me and say: mommy !

A chapter unwritten in this heavenly homily

To which every girl hopes to contribute another.

Eighteen, and my life is over.

—I think that’s as beautiful as Antigone’s laments in Sophocles.

—I have Paul Verlaine’s Fêtes galantes, in a pocket edition. Really strange, very

funny; but, really, adorable. And sometimes he takes serious license, like: And the terrible tigress

. . . is a line in the book. You should buy a little book of his called La Bonne

Chanson: it just came out with Lemerre; I haven’t read it; nothing comes here; but

more than one newspaper has had good things to say about it;

—So good-bye, send me a 25-page letter—general delivery—and right away!

A. Rimbaud

P.S. —Soon, revelations about the life I’ll lead . . . after vacation . . .

TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Paris, September 5, 1870

Cher Monsieur,

What you told me I shouldn’t do, I did: I went to Paris, abandoning my maternal home! I left August 29. Stopping when getting off the train because I was penniless you have never been less than a brother to me: so I ask for the immediate help you’ve offered before. I wrote my mother, the imperial prosecutor, the Charleville chief of police; if you don’t hear anything from me on Wednesday, before the train for Paris leaves from Douai take that train, come here and claim me by letter or go to the prosecutor yourself, beg, vouch for me, pay my debt! Do everything you can, and, when you get this letter, write, you too, I order you, yes, write to my poor mother (quai de la Madeleine, 5, Charlev.) to console her, write me too, do it all! I love you like a brother, I will love you like a father.

Taking your hand, your poor Arthur Rimbaud

From Mazas.

And if you are able to set me free, take me to Douai with [you].

Rimbaud had run away to Paris, fleeing there by train without a ticket. Upon arrival, he was arrested and thrown in jail, wherefrom this letter. Mazas: the Paris prison on boulevard Diderot.

PROTEST LETTER

September 18, 1870

We the undersigned, members of the legion of the sedentary national guard of Douai are protesting against the letter of Monsieur Maurice, mayor of Douai, brought to order on September 18, 1870. In response to the numerous complaints by unarmed members of the national guard, Monsieur the Mayor refers us to the orders given by the Minister of War; in a letter ripe with insinuation, he seems to accuse the Ministers of War and the Interior of ill-will or lack of foresight. Without going so far as to establish ourselves as defenders of a battle already won, we do feel it is our right to assert that the lack of arms at present is attributable only to the lack of foresight and ill-will of the deposed government, to which consequences we are still being subjected. We all should understand the grounds by which the government presiding over the national defense reserves its remaining arms for its soldiers on active duty as well as those on patrol: naturally they all should be armed by the government well before us. Is this the same as saying that three quarters of the national guard cannot be armed, even though they are resolved to defend themselves if attacked? Not at all: they do not wish to remain useless: they must be armed at all costs. It is up to the town council—officials whom we elected—to procure them. The mayor, in such cases, must take the initiative, and, as has already been done in many French communities, he must put in play all means necessary and available to purchase and distribute arms in his community.

Elections for the town council are next Sunday, and we wish to lend our support only to those who, in their words and deeds, will show themselves devoted to our best interests. Now, in our opinion, the Mayor of Douai’s letter, read publicly last Sunday after the review, strove, voluntarily or not, to cast discredit on the government of the national defense, to sow discouragement in our ranks, as if there were nothing remaining of the municipal will: which is why we have felt it necessary to protest against the apparent intentions with this letter.

F. Petit

Protest Letter: penned pseudonymously by Rimbaud in an effort to secure rifles for the national guard that had formed as a result of France’s invasion by Prussia.

TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Charleville, November 2, 1870

Monsieur

—For your eyes only.—

I got back to Charleville the day after leaving you. My mother was here to meet me, and I—am here . . . utterly idle. My mother will be sending me to boarding school, but not until January of ’71.

But! I kept my promise.

I’m dying, decomposing under the weight of platitude, of crap, of gray, of the daily grind. What else would you expect, I stubbornly continue to love free freedom, and . . . so many things that are “so very unfortunate,” am I right? —I should just leave again today; I could do it: I was wearing new clothes, I could have sold my watch, and so hooray for freedom! —But I stayed put! I stayed put! And I will want to leave again and again. And off I’ll want to go, hat, greatcoat, fist in my pockets and away . . . ! But I will stay, I will stay. I didn’t promise that. But I will do it to prove myself worthy of your affection: you said as much. And I will be worthy.

I have such gratitude for you that I wouldn’t be able to express it any more today than I was the other day. I will just have to prove it to you. I will by doing something for you that will kill me—I will give you my word. —I still have so much to say . . .

Your “heartless”

A. Rimbaud

War: Mézières has been besieged. When? No one knows. —I gave your message to M. Deverrière, and, if there is anything else, I will do it. —Sniper fire here and there. The popular mind here is like one stupid, ceaseless itch. The things people say. Depressing.

TO PAUL DEMENY

Charleville, April 17, 1871

Your letter arrived yesterday, the 16th. Thanks. —As for what I asked of you: I must have been out of my mind. Knowing nothing of what I should know, and resolved to doing nothing of what I should do, I am condemned, forever and ever. Live for today, live for tomorrow!

Since the 12th, I’ve been opening the mail for the Progrès des Ardennes: today, sure enough, the newspaper ceased operations. But at least I briefly appeased the mouth of darkness.

Yes, you are happy, you. I’ll say this—whether woman or idea, miserables never find their Sister of Charity.

But today I would suggest you ponder these verses from Ecclesiastes: “And he would have seven flights of madness in his soul, who, having hung his clothes beneath the sun, would groan at the hour of rain,” but I heap scorn upon wisdom and 1830: let’s talk about Paris.

There are a few new things at Lemerre: two poems by Leconte de Lisle, Le Sacre de Paris, le Soir d’une bataille. —By F. Coppée: Lettre d’un Mobile breton. —Mendès: Colère d’un Franc-tireur. —A. Theuriet: L’Invasion. A. Lacaussade: Vœ victoribus. —Poems by Félix Franck, by Émile Bergerat. —A Siège de Paris, really good, by Claretie.

While I was there I read Le Fer rouge, Nouveaux châtiments, by Glatigny, dedicated to Vaquerie; available through Lacroix, probably in both Paris and Brussels.

At La Librairie artistique—from Vermersch’s address—they asked me what was new with you. I said you were still in Abbeville.

Every bookstore had its Siège, its Journal de Siège; Sarcey’s is in its 14th printing; I saw endless streams of photographs and drawings about the Siège; you wouldn’t have believed it. The most interesting were of A. Marie, Les Vengeurs, Les Faucheurs de la Mort; above all Dräner and Faustin’s comic drawings. —As far as theaters went, it was abomination and desolation. —The dailies were represented by Le Mot d’ordre and Le Cri du Peuple, with Vallès’s and Vermersch’s admirable imaginations.

the mouth of darkness: Rimbaud’s nickname for his mother, borrowed from Victor Hugo. “ And he would have seven . . . the hour of rain ” : Actually, from the gospel according to Rimbaud: no such verse exists in Ecclesiastes.

So that was literature from February 25 to March 10. —But I may not have told you anything you didn’t already know.

If so, turn your face towards the lances of rain, the soul towards ancient wisdom.

And may Belgian literature take us under its wing.

Au revoir,

A. Rimbaud

TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Charleville, 13 May 1871

And so you’re a professor again. You’ve said before that we owe something to Society; you’re a member of the brotherhood of teachers; you’re on track. —I’m all for your principles: I cynically keep myself alive; I dig up old dolts from school: I throw anything stupid, dirty, or plain wrong at them I can come up with: beer and wine are my reward. Stat mater dolorosa, dum pendet filius. I owe society something, doubtless—and I’m right. You are too, for now. Fundamentally, you see your principles as an argument for subjective poetry: your will to return to the university trough— sorry!—proves it! But you will end up an accomplished complacent who accomplishes nothing of any worth. That’s without even beginning to discuss your dry-as-dust subjective poetry. One day, I hope—as do countless others—I’ll see the possibility for objective poetry in your principles, said with more sincerity than you can imagine! I will be a worker: it’s this idea that keeps me alive, when my mad fury would have me leap into the midst of Paris’s battles—where how many other workers die as I write these words? To work now? Never, never: I’m on strike. Right now, I’m encrapulating myself as much as possible. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working to turn myself into a seer: you won’t understand at all, and it’s unlikely that I’ll be able to explain it to you. It has to do with making your way toward the unknown by a derangement of all the senses. The suffering is tremendous, but one must bear up against it, to be born a poet, and I know that’s what I am. It’s not at all my fault. It’s wrong to say I think: one should say I am thought. Forgive the pun.

I is someone else. Tough luck to the wood that becomes a violin, and to hell with the unaware who quibble over what they’re completely missing anyway!

You aren’t my teacher. I’ll give you this much: is it satire, as you’d say? Is it poetry? It’s fantasy, always. —But, I beg you, don’t underline any of this, either with pencil, or—at least not too much—with thought.

TORTURED HEART

My sad heart drools on deck,

A heart splattered with chaw:

A target for bowls of soup,

My sad heart drools on deck:

Soldiers jeer and guffaw.

My sad heart drools on deck,

A heart splattered with chaw!

Ithyphallic and soldierly,

Their jeers have soiled me!

Painted on the tiller

Ithyphallic and soldierly.

Abracadabric seas,

Cleanse my heart of this disease.

Ithyphallic and soldierly,

Their jeers have soiled me!

When they’ve shot their wads,

How will my stolen heart react?

Bacchic fits and bacchic starts

When they’ve shot their wads:

I’ll retch to see my heart

Trampled by these clods.

What will my stolen heart do

When they’ve shot their wads?

Which isn’t to say it means nothing. —WRITE BACK.

With affection,

Ar. Rimbaud

LETTER TO PAUL DEMENY

Charleville, May 15, 1871

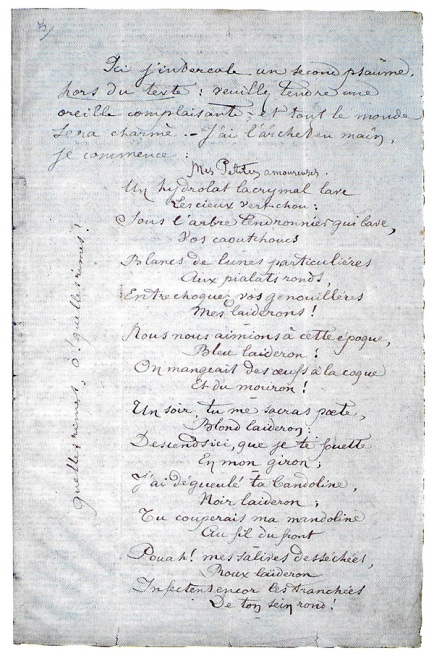

I resolved to provide you with an hour of new literature; I’ll jump right in with a psalm on current events:

THE BATTLE SONG OF PARIS

Spring is here, plain as day,

Thiers and Picard steal away

From what they stole: green Estates

With vernal splendors on display.

May: a jubilee of nudity, asses on parade.

Sèvres, Meudon, Bagneux, Asnières—

New arrivals make their way,

Sowing springtime everywhere.

They’ve got shakos, sabers, and tom-toms,

Not those useless old smoldering stakes,

And skiffs that “ That nev-nev-never did cut . . . ”

Through the reddening waters of lakes.

Now more than ever we’ll band together

When golden gems blow out our knees.

Watch as they burst on our crumbling heaps:

You’ve never seen dawns like these.

Thiers and Picard think they’re artists

Painting Corots with gasoline.

They pick flowers from public gardens,

Their tropes traipsing from seam to seam . . .

They’re intimates of the Big Man, and Favre,

From the flowerbeds where he’s sleeping,

Undams an aqueductal flow of tears: a pinch

Of pepper prompts adequate weeping . . .

The stones of the city are hot,

Despite all of your gasoline showers.

Doubtless an appropriate moment

To roust your kind from power . . .

And the Nouveau Riche lolling peacefully

Beneath the shade of ancient trees,

Will hear boughs break overhead:

Red rustlings that won’t be leaves!

Now, prose on the future of poetry.

All ancient poetry culminated with Greek poetry—Harmonious Life.

From Greece to the romantic movement—the Middle Ages—there are writers and versifiers. From Ennius to Theroldus, from Theroldus to Casimir Delavigne, it’s all rhymed prose, a game, the sloppiness and glory of innumerable ridiculous generations: Racine is the standout, pure, strong, great. Had his rhymes been ruined and his hemistiches muddled, the Divine Dunderhead would be as forgotten today as the next author of the Origins. —After Racine, the game got old. It kept going for two thousand years!

Neither joke nor paradox. Reason fills me with more certainty about all this than a Young France would have been with fury. So the neophytes are free to curse their forebears: it’s their party and the night is young. Romanticism has never been fairly appraised; who would have? Critics!! The romantics, who so clearly prove that the song is infrequently the work of a singer, which is to say rarely is its thought both sung and understood by its singer.

For I is someone else. If the brass awakes as horn, it can’t be to blame. This much is clear: I’m around for the hatching of my thought: I watch it, I listen to it: I release a stroke from the bow: the symphony makes its rumblings in the depths, or leaps fully formed onto the stage. If old fools hadn’t completely misunderstood the nature of the Ego, we wouldn’t be constantly sweeping up these millions of skeletons which, since time immemorial, have hoarded products of their monocular intellects, a blindness of which they claim authorship!

In Greece, as I mentioned, poems and lyres turned Action into Rhythm. Later, music and rhyme became games, mere pastimes. The study of this past proves precious to the curious: many get a kick out of reworking these antiquities: let them. The universal intelligence has, of course, always shed ideas; man harvests a portion of these mental fruits: they measured themselves against them, wrote books about them: so things progressed, man not working to develop himself, not yet awake, or not yet enveloped in the fullness of the dream. Functionaries, writers: author, creator, poet—such a man never existed.

The first task of any man who would be a poet is to know himself completely; he seeks his soul, inspects it, tests it, learns it. And he must develop it as soon as he’s come to know it; this seems straightforward: a natural evolution of the mind; so many egoists call themselves authors; still others believe their intellectual growth is entirely self-induced! But all this is really about making one’s soul into a monster: like some comprachico! Like some man sewing his face with a crop of warts.

I mean that you have to be a seer, mold oneself into a seer. The Poet makes himself into a seer by a long, involved, and logical derangement of all the senses. Every kind of love, of suffering, of madness; he searches himself; he exhausts every possible poison so that only essence remains. He undergoes unspeakable tortures that require complete faith and superhuman strength, rendering him the ultimate Invalid among men, the master criminal, the first among the damned—and the supreme Savant! For he arrives at the unknown! For, unlike everyone else, he has developed an already rich soul! He arrives at the unknown, and when, bewildered, he ends up losing his understanding of his visions, he has, at least, seen them! It doesn’t matter if these leaps into the unknown kill him: other awful workers will follow him; they’ll start at the horizons where the other has fallen!

—more in six minutes—

At this point I’ll insert another psalm from off book: lend a forgiving ear—and everyone will be delighted. —Bow in hand, I begin:

MY LITTLE LOVES

A teary tincture slops

Over cabbage-green skies:

Beneath saplings’ dewy drops,

Your white raincoats rise

With strange moons

And bony spheres,

Knock your knees together

My disgusting dears.

How we loved each other then

My blue, disgusting dear:

We ate eggs and chickenweed . . .

Now you’re no longer here.

One night you named me poet,

My blonde, disgusting dear:

Over my knees I spanked you . . .

Now you’re no longer here.

Your brilliantine made me sick,

My dark, disgusting dear:

Your brow could break a guitar . . .

Now you’re no longer here.

My dry jets of sputum,

O red, disgusting dear,

Fester between your breasts . . .

Though they’re no longer here.

O my little loves, I come

To hate you all the more.

I hope your disgusting tits

Grow ripe with painful sores.

You trampled my stores of caring

Now dance for me once again,

No break is ever past repairing

But Love—broken, ne’er we mend.

My loves’ shoulders dislocate:

An ever-increasing trend.

Stars brand your hobbled hips,

I won’t fall for your tricks again.

And yet, for these sides of beef

I rhymed the lines above:

Their hips I should have broken

Than fill with acts of love.

Guileless clumps of fallen stars

Accumulate in flurries;

You’ll die alone, with God,

Saddled by your worries.

Beneath strange moons

And bony spheres,

Knock your knees together

My disgusting dears!

A.R.

There it is. And please be aware that were it not for fear of making you spend 60 centimes on postage—I who, frozen in fear, have been broke for seven months—would be sending you, Monsieur, my one hundred hexameter “Lovers of Paris,” and my two hundred hexameter “Death of Paris”!—

But I digress:

The poet is really a thief of fire.

Humanity, and even the animals, are his burden; he must make sure his inventions live and breathe; if what he finds down below has a form, he offers form: if it is formless, he offers formlessness. Find the words. —What’s more, given every word is an idea, the day of a single universal language will dawn! Only an academic deader than a fossil could compile a dictionary no matter what the language. Just thinking about the first letter of the alphabet would drive the weak to the brink!

This language will be of the soul, for the soul, encompassing everything, scents, sounds, colors, one thought mounting another. The poet will define the unknown quantity awaking in his era’s universal soul: he would offer more than merely formalized thought or evidence of his march on Progress! He will become a propagator of progress who renders enormity a norm to be absorbed by everyone!

This will be a materialistic future, you’ll see. These poems will be built to last, brimming with Number and Harmony. At its root, there will be something of Greek Poetry to them. Eternal art would have its place; poets are citizens too, after all.

Poetry will no longer beat within action; it will be before it. Poets like this will arrive! When woman will be freed from unending servitude, when she too will live for and by her self, man—so abominable up until now—having given her freedom, will see her become a poet as well! Women will discover the unknown! Will her world of ideas differ from ours? She will find strange, unfathomable, repugnant, delicious things; we will take them in, we will understand.

In the interim, we require new ideas and forms of our poets. All the hacks will soon think they’ve managed this. —Don’t bet on it!

The first romantics were seers without even really realizing it: their soul’s education began by accident: abandoned trains still smoking, occasionally taking to the tracks. Lamartine was a seer now and again, but strangling on old forms. Hugo, too pigheaded, certainly saw in his most recent works: Les Misérables is really a poem. I’ve got Les Chatiments with me; Stella gives some sense of Hugo’s vision. Too much Belmontet and Lamennais with their Jehovahs and colonnades, massive crumbling edifices.

For us, a sorrowful generation consumed by visions and insulted by his angelic sloth, Musset is fourteen times worse! O the tedious tales and proverbs! O his Nuits ! His Rolla, Namouna, La Coupe. It’s all so French, which is to say unbearable to the n th degree; French, but not Parisian. Another work by that odious genius who inspired Rabelais, Voltaire, and Jean La Fontaine, with notes by M. Taine! How vernal, Musset’s mind! And how delightful, his love! Like paint on enamel, his dense poetry! We will savor French poetry endlessly, in France. Every grocer’s son can reel off something Rollaesque, every seminarian has five hundred rhymes hidden in his notebook. At fifteen, these passionate impulses give boys boners; at sixteen, they’ve already resolved to recite their lines with feeling; at eighteen, even seventeen, every schoolboy who can write a Rolla does— and they all do! Some may even still die from it. Musset couldn’t do anything: they were mere visions behind the gauze curtains: he closed his eyes. French, half-dead, dragged from tavern to school desk, the beautiful corpse has died, and, ever since, we needn’t waste our time trying to rouse him with our abominations!

The second romantics are true seers; Th. Gautier, Lec. de Lisle, Th. de Banville. But to explore the invisible and to hear the unheard are very different from reviving the dead: Baudelaire is therefore first among seers, the king of poets, a true God. And yet even he lived in too aestheticized a world; and the forms for which he is praised are really quite trite: the inventions of the unknown demand new forms.

In the rut of old forms, among innocents, A. Renaud did a Rolla; L. Grandet did his; the Gauls and Mussets; G. Lafenestre, Coran, Cl. Popelin, Soulary, L. Salles; schoolboys Marc, Aicard, Theuriet; the dead and the dumb, Autran, Barbier, L. Pichat, Lemoyne, the Deschamps, the Desessarts; the journalists, L. Cladel, Robert Luzarches, X. de Ricard; the fantasists, C. Mendes; the bohemians; the women; the prodigies, Leon Dierx, Sully Prudhomme, Coppée; the new so-called Parnassian school has two seers, Albert Mérat and Paul Verlaine, a true poet. —There it is. So I work to turn myself into a seer. And conclude with a pious song.

SQUATTING

Later, when he feels his stomach grumble,

Brother Milotus—an eye on the skylight

Where bright as a scoured pot the sun

Shoots him a migraine and briefly blinds him—

Shifts his priestly belly beneath the sheets.

He thrashes about beneath the covers

And sits up, knees against his trembling belly,

Upset like an old man who’s swallowed his snuff,

Because he still must hike his nightshirt up

Over his hips, clutching the handle of his chamberpot.

Now, squatted, shaking, his toes

Curled, shivering in the bright sunlight that plasters

Brioche-yellow patches on the paper windowpanes;

And the fellow’s shiny nose ignites

With light, like a fleshy polyp.

The fellow simmers by the fire, his arms in a knot, his lip

Hanging to his belly: he feels his thighs slipping towards the fire,

And his chausses glow red hot, and his pipe goes cold;

Something like a bird barely stirs

In his belly, serene as a pile of tripe.

Around him, a jumble of beaten furniture sleeps

Amidst filthy rags and dirty bellies;

Stools like strange toads sit hunched

In dark corners: sideboards with mouths like cantors

Gaping with carnivorous sleep.

Sickening heat crams into the narrow room;

The fellow’s head is stuffed with rags.

He listens to the hairs growing on his moist skin,

And, at times, ridiculous hiccups

Escape, shaking his wobbly stool . . .

And at night, in the light of the moon

That drools its beams onto the curves of his ass,

A shadow squats, etched onto a backdrop

Of rosy snow, like a hollyhock . . .

Remarkable: a nose hunts for Venus in the deep dark sky.

You’d be a son-of-a-bitch not to respond: quickly: in a week I’ll be in Paris, maybe.

Au revoir, A. Rimbaud

TO PAUL DEMENY

Charleville, June 10, 1871

POETS, AGE SEVEN

And the Mother, closing the workbook,

Departed satisfied and proud, without noticing,

In blue eyes beneath a pimply forehead,

The loathing freighting her child’s soul.

All day he sweated obedience; clearly

Intelligent; and yet, black rumblings, hints

Of bitter hypocrisies, hidden, underneath.

In shadowy corridors hung with moldy drapes

He’d stick out his tongue, thrust his fists

In his pockets, shut his eyes till he saw spots.

A door opened onto the night: by lamplight

You could see him, up there, moaning from the banister,

Beneath a bay of light under the roof. Above all,

In summer, beaten and dumb, he was bent

On locking himself in cool latrines:

He could think there, peacefully, filling his lungs.

In winter, when the garden behind the house

Was bathed in the day’s fragrances, illunating,

Lying down at the foot of a wall, interred in clay

He pushed on his eyes until they swam with visions,

Listening to the rustling of mangy espaliers.

What a shame! His only friends were bareheaded runts

Whose eyes leaked onto their cheeks, who hid

Skinny fingers mottled yellow-black with mud

Beneath ragged clothes that stunk of the shits,

And who spoke as blandly as idiots.

And when his Mother found him wallowing among them

She was shocked; but seeing such tenderness

In her child muted her surprise. For an instant:

Her blue eyes lied.

At seven years old, he wrote novels

About life in the desert, where Freedom reigns,

Forests, suns, riverbanks, plains. —Inspiration

Came in the form of illustrated papers where he

Blushingly saw laughing girls, from Italy and Spain.

When the daughter of the laborers next door

Came by, eight years old, wild brown eyes,

In a calico dress, he backed her into a corner

And the little brute pounced onto his back,

Pulling his hair, and so, while under her,

He bit her ass, since she never wore panties;

—And bruised by her fists and heels,

He carried the taste of her skin back to his room.

He hated dreary December Sundays,

His hair greased flat, sitting on a high mahogany table,

Reading from a Bible with cabbage-green edges;

Dreams overwhelmed him each night in his little room.

He didn’t love God; instead, the men returning to the suburbs

After dark, in jackets, in the tawny dusk,

Where the town criers, after a trio of drumrolls,

Would stir up crowds with edicts and laughter.

He dreamt meadows of love, where luminous swells

Of nourishing scents and golden pubescence

All move about calmly and take wing!

And as he especially relished darkness,

When he was alone in his room, shutters shut,

High and blue, painfully pierced by damp,

He read his endlessly pondered novel,

Overflowing with heavy ochre skies and drowning forests,

Flowers of flesh scattered through the starry woods,

Vertigo, collapse, routs in battle and lasting pity.

—While the noise in the neighborhood continued

Below—alone, reclined on cream canvas,

He had a violent vision of setting sail.

A.R. 26 May 1871

THE POOR AT CHURCH

Parked on oak benches in church corners

Warmed by stale breath, eyes fixed

On the chancel’s glittering gold, the choir’s

Twenty mouths mumble pious hymns;

Inhaling in the scent of melting wax like the aroma

Of baking bread, the Happy Poor,

Humiliated like beaten dogs, make stubborn dumb prayers

To the good Lord, their patron and master.

After six dark days of suffering in God’s name,

The women don’t mind wearing the benchwood smooth.

In dark cloaks they cradle ugly children

Who cry as if on the brink of death.

Dirty dogs dangle from these soup eaters,

Prayer in their eyes but without a prayer

They watch as a group of girls parades by

Wearing ugly hats.

Outside: cold; hunger; carousing men.

But for now all’s well. One more hour; then,

Unmentionable evils! —For now, wattled old women

Surround them groaning, whining, whispering:

Idiots abound, and epileptics

You’d avoid in the street; blind men

Led by dogs through the squares

Nose through crumbling missals.

And all of them, drooling a dumb beggars’ faith,

Recite an endless litany to a yellow Jesus

Who dreams on high amidst stained glass,

Far from gaunt troublemakers and miserable gluttons,

Far from scents of flesh and moldy fabric,

This dark defeated farce of foul gestures;

—And prayer blossoms with choice expressions,

And mysticisms take on hurried tones,

Then, from the darkened naves where sunlight dies,

Women from better neighborhoods emerge,

All dim silk, green smiles, and bad livers—O Jesus!—

Dipping their long yellow fingers in the stoups.

June 1871

Look—don’t be mad—at these notions for some funny doodles: an antidote to those perennially sweet sketches of frolicking cupids, where hearts ringed in flames take flight, green flowers, drenched birds, Leucadian promontories, etc. . . . —These triolets are also as good as gone . . .

Perennially sweet sketches

And sweet verse.

Look—don’t be mad—

HEART OF STONE

My sad heart drools on deck,

A heart splattered with chaw:

A target for bowls of soup,

My sad heart drools on deck:

Soldiers jeer and guffaw.

My sad heart drools on deck,

A heart splattered with chaw!

Ithyphallic and soldierly,

Their jeers have soiled me!

Painted on the tiller

Ithyphallic and soldierly.

Abracadabric seas,

Cleanse my heart of this disease.

Ithyphallic and soldierly,

Their jeers have soiled me!

When they’ve shot their wads,

How will my stolen heart react?

Bacchic fits and bacchic starts

When they’ve shot their wads:

I’ll retch to see my heart

Trampled by these clods.

What will my stolen heart do

When they’ve shot their wads?

So that’s what I’ve been up to.

I have three requests:

Burn, I’m not kidding, and I hope you will respect my wishes as you would a man on his deathbed, burn all the poems I was dumb enough to send you when I was in Douai: be so kind as to send me, if you can and if you want to, a copy of your Glaneuses, which I want to reread and is impossible for me to buy since my mother hasn’t given me a penny in six months —oh too bad! Finally, please respond, anything at all, to this and my previous letter.

I wish you a good day, which is something.

Write to: M. Deverrière, 95 sous les Allés, for

A. Rimbaud.

TO GEORGES IZAMBARD

Charleville, July 12, 1871

Cher Monsieur,

[So you’re going swimming in the ocean], you’ve been [sailing . . . Boyards: that seems very far away, so you’ve had enough of my jealousy, of hearing how I’m suffocating here!] Anyway, I’m driving myself to unspeakable distraction and can barely get anything down.

Nonetheless, I need to ask you something: an enormous debt—to a bookstore—has fallen upon me, and I don’t have a dime to my name. I have to sell back my books. You must remember that in September of 1870, having come—for me—to try to soften my mother’s hardened heart, you brought, upon my recommendation, [several books, five or six, that in August I had brought to you, for you.]

So: do you still have Banville’s Florise and Exiles ? Given I must sell back my books to the bookstore, it would help me to get these two back: I have some other books of his here; with yours, they would make up a small collection, and collections sell better than books by themselves.

Do you have Les Couleuvres ? I would be able to sell this as new. —Did you hold onto Nuits persanes ? An appealing title even second-hand. Do you still have the Pontmartin? There are still people around here who would buy his prose. —What about Les Glaneuses ? Ardennais schoolchildren will spend three francs to fiddle in his blue skies. I would be able to convince my crocodile that the purchase of this collection would bring considerable benefits. I’d be able to put the best face on the least book. The audacity of all this second-hand shenanigans is wearying.

If you knew the extent to which my debt of 35 fr. 25 c. was driving my mother to her worst, you wouldn’t hesitate to get those books to me. You would send the bundle care of M. Deverrière, 95 sous les Allées, which I would be waiting for. I will pay back your postage, and I would be overoverflowing with gratitude!

The brackets indicate sentences destroyed by glue, which Izambard reconstructed from memory.

Were there any other volumes that would be out of place in the library of a professor with which you felt like parting, feel free. But hurry, please, I’m under the gun.

Cordially, and with thanks in advance.

A. Rimbaud

P.S. —In a letter from you to M. Deverrière, I noticed that you were worried about your crates of books. He will get them to you as soon as you tell him where to send them.

A handshake in thought.

A.R.

TO PAUL DEMENY

Charleville, August 28, 1871

You would suggest I say my prayers again: fine. This is my complaint in full. I’m trying to chose peaceful words: but that isn’t my strong suit. But here we go.

The situation as it stands: a year ago, I abandoned ordinary life in favor of one you now know well. Trapped without end in this unspeakable Ardennais countryside, seeing no one, consumed by revolting, inane, dogged, mysterious work, answering questions with silence, answering rude, cruel remarks with silence, attempting to appear dignified in my extralegal circumstances, and ending up provoking appalling resolutions from a mother as set in her ways as seventy-three administrations in lead helmets.

She wanted to make me work—for good, in Charleville (Ardennes)! Either take a job on such-and-such a day, or hit the road. —I rejected that life, without giving my reasons: it would have been pathetic. And until now, I had been able to ignore her schedule. She has come to this: she longs for little more than my immediate departure, my flight! Poor, inexperienced, I would end up in a house of correction. And from that moment forward, not a word from me would be heard!

This is the rag of disgust that has been shoved in my mouth. Simple as that.

I am not asking for anything, only information. I want to be free when I work: but in the Paris I love. Here: I am a pedestrian, no more, no less; I come to the great city without the least material resource: but you have said in the past: Whosoever wishes to work for fifteen sous a day can go here, do that, live like so. I’ll go, do, live. I begged you to advise me on what were the least demanding occupations, as though this takes up a great amount of time. Poetic absolution, this materialist see-saw has its charms. I am in Paris: I need some savings! You know I’m sincere, right? To me, this all seems so strange that I have to stress just how serious I am.

I had the idea above: it was the only reasonable alternative: I’ll put it another way: I’m determined, I do my best, I speak as well as any other malcontent. Why scold a child who, not blessed with much zoological understanding, wishes for a five-winged bird? Why not have him believe in six-tailed birds with three beaks? Why not loan him a family Buffon: that would cure him of his delusions.

So, uncertain as to how you might respond, I’ll put an end to my explanations and put my faith in your experienced hands, in your blessed kindness, in awaiting your letter, in awaiting what you think of my ideas—if you will think of them . . .

Would you tolerate seeing a few samples of my work?

A. Rimbaud

Buffon: Georges-Louis Buffon (1707–88), writer of a classic work of natural history.

TO PAUL VERLAINE

[Charleville, September 1871]

[ . . . ] I have been planning a long poem, but I can’t work in Charleville any more. But I’m without resources, so I can’t come to Paris. My mother is widowed and extremely religious. She gives me ten centimes a week, to pay for my church pew.

[ . . . ] dirty girl [ . . . ]

[ . . . ] less trouble than a Zanetto [ . . . ]

This letter and the next are fragmentary reconstructions of letters Rimbaud sent to Paul Verlaine (1844–1896). Verlaine was an influential poet of the day to whom Rimbaud wrote requesting help (as he did of Banville). Verlaine’s poetic posterity rests on the collections Fêtes galantes and Romances sans paroles, but his fame has come for being remembered as the teenaged Rimbaud’s lover. These letters have been cobbled together from separate published recollections by Verlaine and his wife, Mathilde, of letters that were destroyed. The “Zanetto” reference— a fey boy commedia dell’arte archetype that functioned as a seducer—has been fodder for generations of writers who claim this was Rimbaud’s code to Verlaine that he would provide his potential patron with pleasurable recompense. Undependable.

TO PAUL VERLAINE

Charleville, April 1872

[ . . . ] Right now work is about as far from my thoughts as my fingernails are from my eyes. Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit! Tough shit!

When you see me actually eat shit, then only you will no longer think that I am expensive to feed! . . .

TO ERNEST DELAHAYE

The Big Shitty, Juneteenth 1872

Yes, life in the Ardennais cosmorama is filled with surprises. I do not miss this province where we eat flour and mud, where we drink local wine and beer. You are perfectly justified in continuing to denounce it. But here: distillation, composition, narrow-mindedness; and the oppressive summers: the heat isn’t without respite, but given that good weather is in everyone’s interests, and that everyone is a pig, I hate how summer kills me when it appears even briefly. I’m so thirsty you would think I have gangrene: Belgian and Ardennais rivers, caves, these I miss.

There is one place to drink here I like. Long live the Academy of Abseenth, however surly the waiters! Such delicate, tremulous attire— drunkenness delivered by abseenth, that glacial sage! All so we may sleep in shit when we’re through.

The whining never changes! What is for certain: fuck Perrin. And why not on the bar of the Café de l’Univers, whether it faces the square or not. —My greatest wish is that the region were occupied and squeezed tighter and tighter. But this is a commonplace.

The worst is that all of this will bother you as much as it will. It seems for the best that you read and walk as much as possible. Reason enough not to remain confined to offices and homes. Mindlessnesses must be given free reign, far from confinement. I am not about to be selling balm, but I imagine habit isn’t much consolation on the worst days.

Now I’m crossing through night. Midnight to five A.M. The past month, my room, rue Monsieur-le-Prince, overlooking a garden in the Lycée Saint-Louis. There were enormous trees beneath my narrow window. At three A.M., the candle dimmed: all the birds in the trees called out together: the end. No more work. I had the trees to look at, the sky, held in this unspeakable hour, morning’s first. I saw the lycée dormitories, utterly silent. And already there was the wonderful melodic staccato of the carts on the streets. —I smoked my hammer pipe, spitting on the tiles, my room high in the garret. At five A.M., I went down to buy bread: that’s the time. Workers are everywhere. For me, it’s the time of day to go get drunk at the wine merchants’. I came back home to eat, and then went to sleep at seven A.M., when the sun stirs the wood lice from under the tiles. The first summer morning, and the December nights, that’s what always delighted me here.

But now I have a pretty room, on an endless courtyard, but three meters square. —La rue Victor Cousin and the Café Bas-Rhim form a corner on the Place de la Sorbonne, and face rue Soufflot on the other side. —There I drink water all night, I don’t see the dawn, I don’t sleep, I suffocate. So there it is.

Your complaints will be lodged, remedy granted! And don’t forget to shit on La Renaissance, that arts and letters daily, should you come across it. Until now I’ve been able to avoid those shitty slickers from home. And fuck the seasons too.

Courage.

A.R.

From

THE LETTERS OF ARTHUR RIMBAUD

I PROMISE TO BE GOOD

RIMBAUD COMPLETE

VOLUME II

TRANSLATED,EDITED,AND

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

WYATT MASON

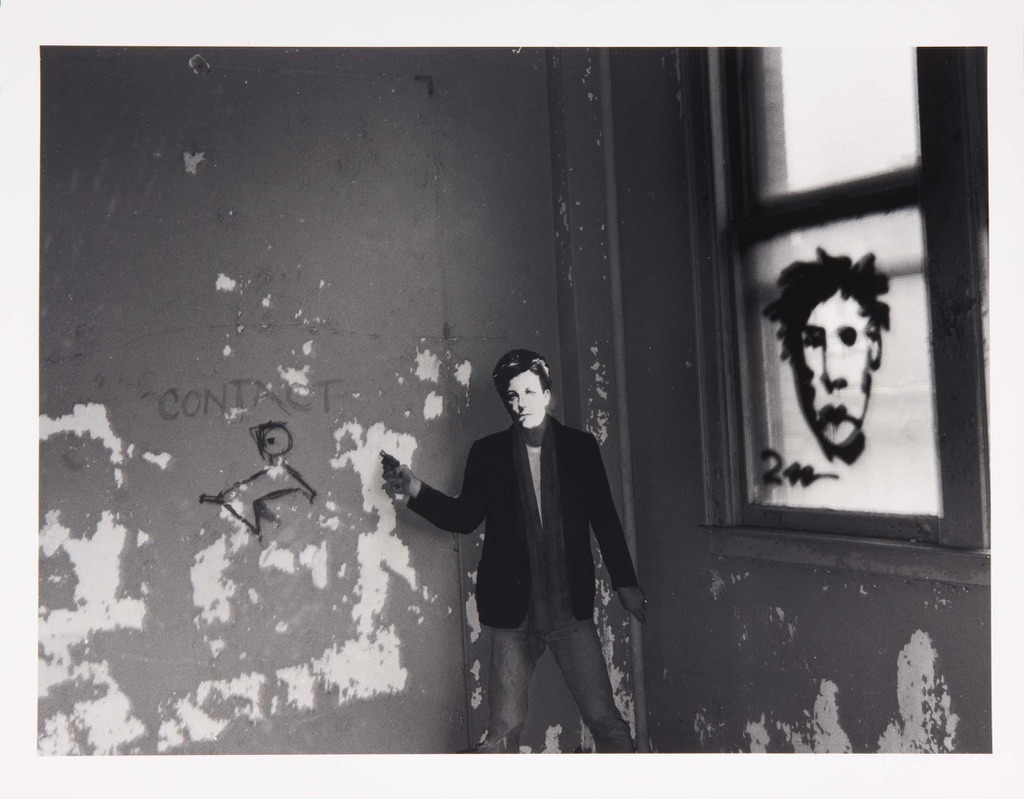

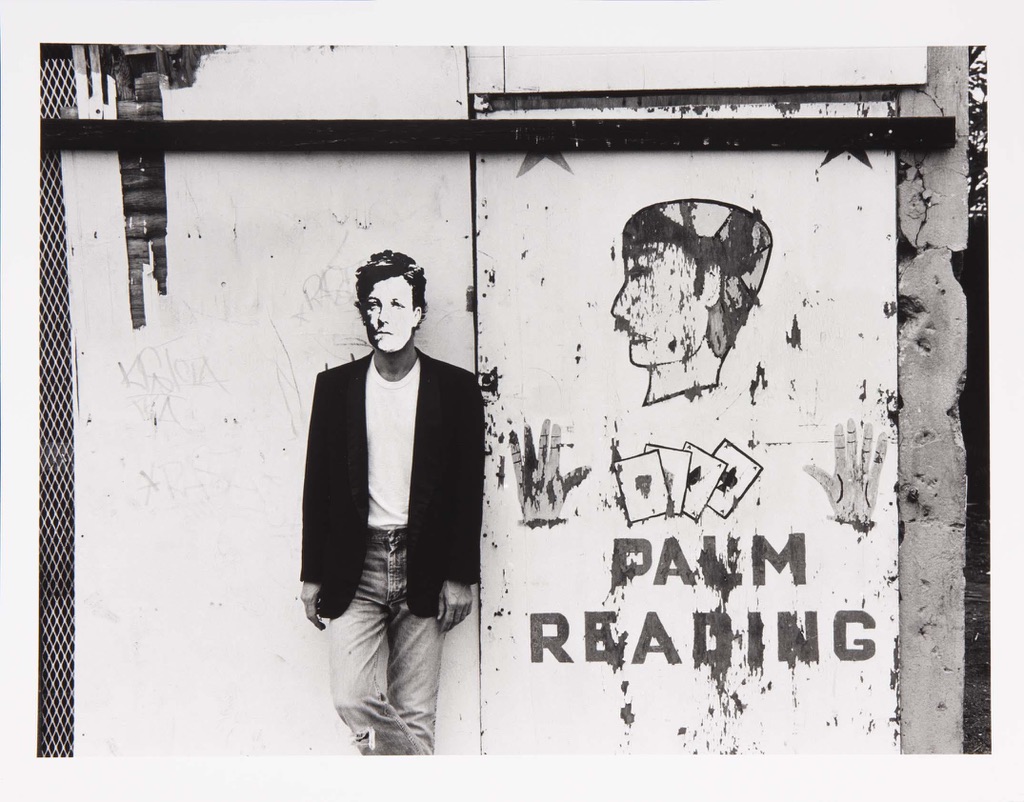

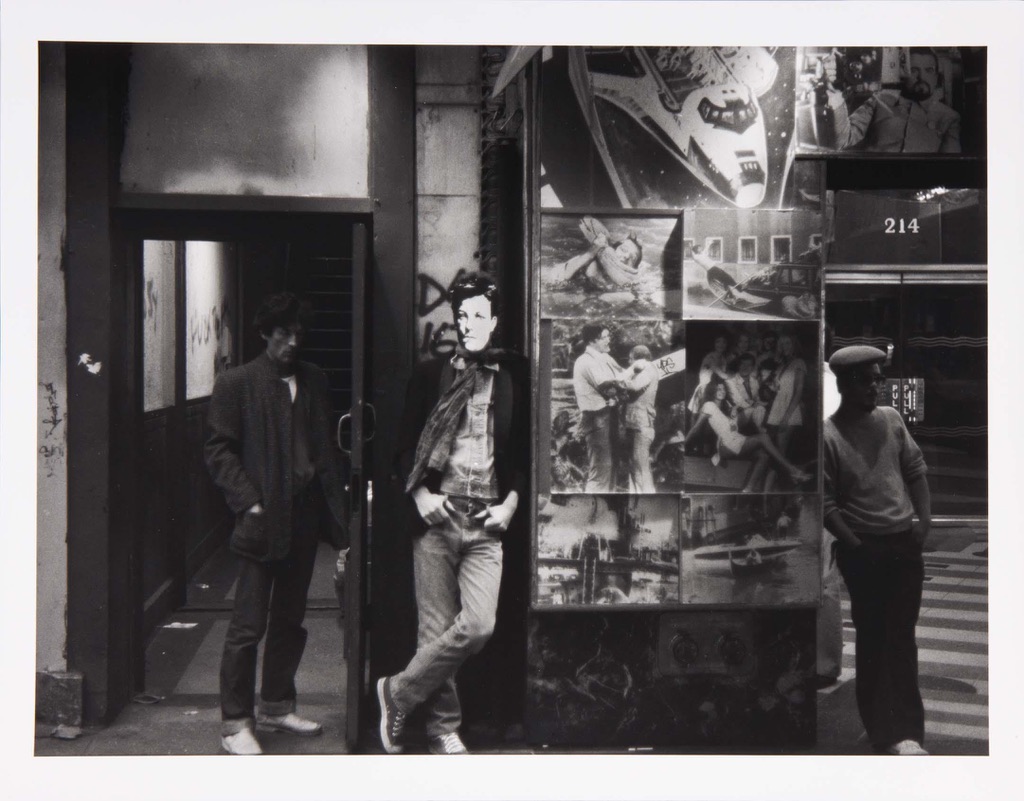

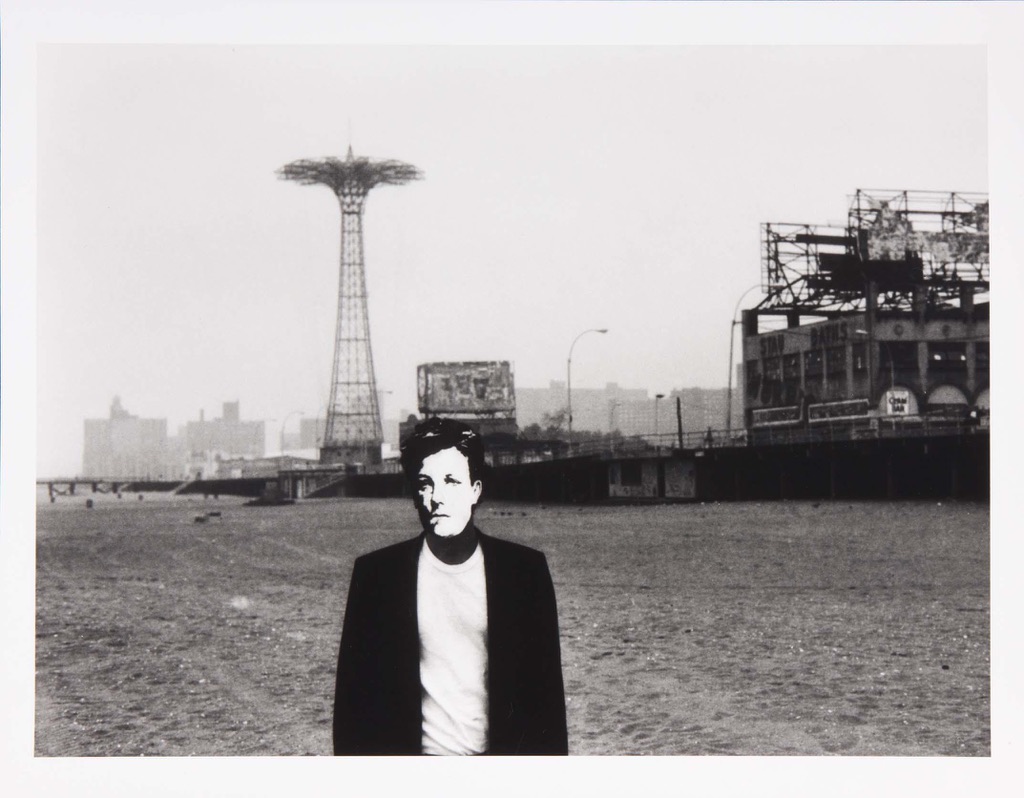

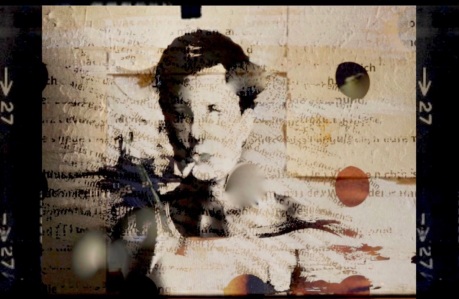

IMAGES BY DAVID WOJNAROWICZ

ARTHUR RIMBAUD IN NEW YORK

Sean Bonney | Letter on Poetics (after Rimbaud)

So I see you’re a teacher again. November 10th was ridiculous, we were all caught unawares. And that “we” is the same as the “we” in these poems, as against “them”, and maybe against “you”, in that a rapid collectivising of subjectivity equally rapidly involves locked doors, barricades, self-definition through antagonism etc. If you weren’t there, you just won’t get it. But anyway, a few months later, or was it before, I can’t remember anymore, I sat down to write an essay on Rimbaud. I’d been to a talk at Marx House and was amazed that people could still only talk through all the myths: Verlaine etc nasty-assed punk bitch etc gun running, colonialism, etc. Slightly less about that last one. As if there was nothing to say about what it was in Rimbaud’s work – or in avant-garde poetry in general – that could be read as the subjective counterpart to the objective upheavals of any revolutionary moment. How could what we were experiencing, I asked myself, be delineated in such a way that we could recognise ourselves in it. The form would be monstrous. That kinda romanticism doesn’t help much either. I mean, obviously a rant against the government, even delivered via a brick through the window, is not nearly enough. I started thinking the reason the student movement failed was down to the fucking slogans. They were awful. As feeble as poems. Yeh, I turned up and did readings in the student occupations and, frankly, I’d have been better off just drinking. It felt stupid to stand up, after someone had been doing a talk on what to do if you got nicked, or whatever, to stand up and read poetry. I can’t kid myself otherwise. I can’t delude myself that my poetry had somehow been “tested” because they kinda liked it. Because, you know, after we achieved political understanding our hatred grew more intense, we began fighting, we were guided by a cold, homicidal repulsion, and very seldom did we find that sensation articulated in art, in literature. That last is from Peter Weiss. I wondered could we, somehow, could we write a poem that (1) could identify the precise moment in the present conjuncture, (2) name the task specific to that moment, ie a poem that would enable us to name that decisive moment and (3) exert force inasmuch as we would have condensed and embodied the concrete analysis of the concrete situation. I’m not talking about the poem as magical thinking, not at all, but as analysis and clarity. I haven’t seen anyone do that. But, still, it is impossible to fully grasp Rimbaud’s work, and especially Une Saison en Enfer, if you have not studied through and understood the whole of Marx’s Capital. And this is why no English speaking poet has ever understood Rimbaud. Poetry is stupid, but then again, stupidity is not the absence of intellectual ability but rather the scar of its mutilation. Rimbaud hammered out his poetic programme in May 1871, the week before the Paris Communards were slaughtered. He wanted to be there, he kept saying it. The “long systematic derangement of the senses”, the “I is an other”, he’s talking about the destruction of bourgeois subjectivity, yeh? That’s clear, yeh? That’s his claim for the poetic imagination, that’s his idea of what poetic labour is. Obviously you could read that as a simple recipe for personal excess, but only from the perspective of police reality. Like, I just took some speed, then smoked a joint and now I’m gonna have a pepsi, but that’s not why I writing this and its not what its about. The “systematic derangement of the senses” is the social senses, ok, and the “I” becomes an “other” as in the transformation of the individual into the collective when it all kicks off. Its only in the English speaking world, where none of us know anything except how to kill, that you have to point simple shit like that out. In the enemy language it is necessary to lie. & seeing as language is probably the chief of the social senses, we have to derange that. But how do we get to that without turning into lame-assed conceptualists trying to get jiggy with their students. You know what, and who, I mean. For the vast majority of people, including the working class, the politicised workers and students are simply incomprehensible. Think about that when you’re going on about rebarbative avant-garde language. Or this: simple anticommunication, borrowed today from Dadaism by the most reactionary champions of the established lies, is worthless in an era when the most urgent question is to create a new communication on all levels of practice, from the most simple to the most complex. Or this: in the liberation struggles, these people who were once relegated to the realm of the imagination, victims of unspeakable terrors, but content to lose themselves in hallucinatory dreams, are thrown into disarray, re-form, and amid blood and tears give birth to very real and urgent issues. Its simple, social being determines content, content deranges form etc. Read Rimbaud’s last poems. They’re so intensely hallucinatory, so fragile, the sound of a mind at the end of its tether and in the process of falling apart, the sound of the return to capitalist business-as-usual after the intensity of insurrection, the sound of the collective I being pushed back into its individuality, the sound of being frozen to fucking death. Polar ice, its all he talks about. OK, I know, that just drags us right back to the romanticism of failure, and the poete maudite, that kinda gross conformity. And in any case, its hardly our conjuncture. We’ve never seized control of a city. But, I dunno, we can still understand poetic thought, in the way I, and I hope you, work at it, as something that moves counter-clockwise to bourgeois anti-communication. Like all of it. Everything it says. We can engage with ideas that have been erased from the official account. If its incomprehensible, well, see above. Think of an era where not only is, say, revolution impossible, but even the thought of revolution. I’m thinking specifically of the west, of course. But remember, most poetry is mimetic of what some square thinks is incomprehensible, rather than an engagement with it. There the phrase went beyond the content, here the content goes beyond the phrase. I dunno, I’d like to write a poetry that could speed up a dialectical continuity in discontinuity & thus make visible whatever is forced into invisibility by police realism, where the lyric I – yeh, that thing – can be (1) an interrupter and (2) a collective, where direct speech and incomprehensibility are only possible as a synthesis that can bend ideas into and out of the limits of insurrectionism and illegalism. The obvious danger being that disappeared ideas will only turn up ‘dead’, or reanimated as zombies: the terrorist as a damaged utopian where all of the elements, including those eclipsed by bourgeois thought are still absolutely occupied by that same bourgeoisie. I know this doesn’t have much to do with ‘poetry’, as far as that word is understood, but then again, neither do I, not in that way. Listen, don’t think I’m shitting you. This is the situation. I ran out on ‘normal life’ around twenty years ago. Ever since then I’ve been shut up in this ridiculous city, keeping to myself, completely involved in my work. I’ve answered every enquiry with silence. I’ve kept my head down, as you have to do in a contra-legal position like mine. But now, surprise attack by a government of millionaires. Everything forced to the surface. I don’t feel I’m myself anymore. I’ve fallen to pieces, I can hardly breathe. My body has become something else, has fled into its smallest dimensions, has scattered into zero. And yet, as soon as it got to that, it took a deep breath, it could suddenly do it, it had passed across, it could see its indeterminable function within the whole. Yeh? That wasn’t Rimbaud, that was Brecht, but you get the idea. Like on the 24th November we were standing around, outside Charing Cross, just leaning against the wall etc, when out of nowhere around 300 teenagers ran past us, tearing up the Strand, all yelling “WHOSE STREETS OUR STREETS”. Well it cracked us up. You’d be a pig not to answer.