Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov, 1: Letters and Theoretical Writings: PDF

Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov, 2: Prose, Plays, and Supersagas: PDF

Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov, 3:

Selected Poems: PDF

Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov

Translated by Paul Schmidt

Edited by Ronald Vroon

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 1997

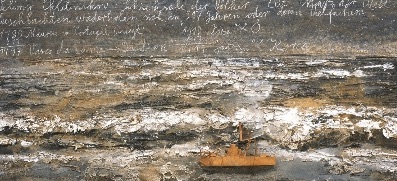

Images by

Anselm Kiefer, for Velimir Khlebnikov

Velimir Khlebnikov and ‚Displacement‘ as Poetics

By Angelina Saule

For Khlebnikov, the theoretical foundation does not exactly sum up his aesthetics and ideas, but is more of a code to slovotvorchestvo (Futurist ‘word creation’), where ‘languages will remain for art and will be freed from a humiliating burden, [that] we are tired from hearing.’ Introducing the idea of language as a benign and malleable force sans frontiers, Khlebnikov does not seem confined to the landscape of the urban, industrial aesthetics usually associated with Futurism. Literary parallelism, for him, is not only between the gentrified, combustive energy of cities, but can also be exchanged and melded through national folk motifs, elements, allusions and linguistic borrowings.

In trying to determine this accentuation of defamiliarisation (ostraneniye) in Khlebnikov’s world, it is important to explore the idea of ‘the word as such’, where the word itself is an object, evoking the possibility to refer to everything that hasn’t yet been proposed, as signage to a copious relation between one thing and another. The linguistic sign represents what is unsaid: an univocal identity of meaning; the illicit and repressed are the attempt of the unconscious of language to voice itself – in itself an impossibility. Khlebnikov’s word-experiments – for example the misleading use of suffixes and prefixes forming from the same root words, the invention of neologisms, or his attempts to create new Russian terms in exchange for long-borrowed foreign terms – all bring about a sense of defamiliarisation with poetic language. His experiments were a serious attempt to recreate a psychotropic world of folklore with the means of high art: a mediation between fairy tales (skazki), folk culture, the cosmopolitan, a blur of intertextual allusions from the world’s literary canon, as well as the languages that comprise world culture.

Khlebnikov was also devoted to the rational, ‘scientific’ relations of the word, confounding any element of emotion. He created mathematical systems to determine the secreted meaning of individual letters within the alphabet and, in one essay, he makes a distinction between ‘the language of general understanding’ (yazik ponimanie) and ‘the language of trans-reason’ (zaumnyi yazik) to prove that his quasi-equations are actual eternal structures to language. (He also surveyed the different consonant sounds in other languages to prove that these structures existed other than in Russian.) Like Balmont, Khlebnikov was fascinated by ‘the primitive stage of language’1, bringing this pre-verbal manner to the Russian language and to Russian poetics, creating a poetic revolution. Poetics would not only become strange by returning to Slavic folk motifs and elements but also by returning to the root of language. Khlebnikov’s word formations raised the level of objectification that could be utilised in Russian grammar and vocabulary in order to create an unexpected aspect of sound to the ear, to haul out the eternal mystery within language itself, stripping it back to its barest bones of groundless, arbitrary meaning.

Khlebnikov’s notion of the ‘word as such’ is an attempt to discover this ‘something’ intrinsic to language itself – perhaps language itself being zaum. ‘Zaum’ was a poetic attempt by Khelbnikov and Alexander Kruchenikh to create a universal language, where a bodily function, an expression of emotion, or any other phenomenon could be expressed by the hyperbolic usage of a word. Zaum was a revolutionary practice to rupture language by going back to the materiality of the word, taking it beyond itself to a pre-foetal and timeless state. It was created at a time that the culture itself was on the verge of war and revolution at the beginning of the 20th century. By emphasising an unusual register of words and their relations to one another, Khlebnikov has evoked insight into the world of words: this infinite poetics and the internal networks within language to unite people all over the world is a concept echoed in many of Khlebnikov’s essays. It is not only his theoretical assertions, but also his baffling semantic structures, which elucidate a mural of soundshapes (‘zvukopis’), which widen and decentre the scope of play abundant with personifications, accents, and obsolete Russian words.

In Lacan’s theory of subjectivity, the self is necessarily divided, intertwining with that which (or whomever) is believed to be other to itself: the Self cannot see itself except through the agency of the other. In his essays from the collection Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan introduces the concept of vision and how internal it is to the structure of our desire and our perception of the desired other. ‘The Gaze’ is an opening; it is not a singular act of observing in a quasi-Kantian model: in Lacanian terms, the concept of the gaze is a point of loss and a series of relations. This relation to things is where ‘something slips, passes, is transmitted, from stage to stage, and is always to some degree eluded in it – that is what we call the gaze’.2

This consolidation and loss of self via the gaze is a construct that benefits readings of poems such as ‘Ra’, whom we find ‘seeing his own eye in the red swamp/ contemplating his dream and himself.’ The poem puts forward the question: who is Ra really looking at? The fixation on others, the hallucinogenic relations that sprout from each and every gaze in the poem – ‘a thousand eyes of the Volga,’ which somehow subsume one eye, although it is not clear whose, by this stage. These malleable notions of the self and how they co-exist between elements, gods, and folkloric motifs require a psychoanalytic tool of interpretation in order to lead to an interrogation of the notion of the self, unfolding as it does in the poems.

Lacan’s essay ‘Subversion of the Subject and the Dialect of Desire’ in Ecrits also provides a theoretical conception of the desiring subject, one in which I frame readings of the speaking ‘I’ in the Persian poems. The representation of subjectivity as shaped by a projection of otherness in the poem can thus be related to the idea of Lacanian desire.

Khlebnikov’s notion of culture is itself not entirely Euro-centric or Russo-centric: culture is something transitional, a declamation of primordial world revolting against the destruction of ‘bourgeois society’ Although Khlebnikov was nurtured by the Futurists’ leap to reveal, defy and invade the unknown and the unexpected, his extraordinary articles, passages and poetic references were devoted to the expressive possibilities that other cultures and languages could bring to the poetic revolution of the Russian language, thus transcending other Futurists in this regard. In order to analyse and understand Khlebnikov’s work, there has to be some understanding of his ideas of language and culture, and his attempts to apply these concepts in his poems.

The fundamental concept of the materiality of the word central to Khlebnikov’s poetics requires clarification. In determining this materiality of the word becoming the space of the word (‘the word as such’ as theorised by Khlebnikov), which is not fully formed, we are led to a poetics of ‘displacement’: where language, words, units, morphemes and syllables are not autonomous, but a space. (For an example of which, Khlebnikov coined the term ‘soundshape’ (zvukopis), which is always in a flux of multiplicity and displaced from its familiar, clichéd usage.)

In order to define ‘displacement’ and why it is utilised in the analysis of the works of Khlebnikov, Deleuze and Guittari’s notion of the ‘rhizome’ has been drawn upon, as it is a theoretical construct that assumes the diverse forms of language as a chain of actions, an event ceaselessly ‘othered’, a channel open to change. Their method of the rhizome is conceived of as a weed of multiplicity, infinite in dimension, encompassing subject and object, image and world, and holding the potential possibilities of signification projected within language. The rhizome is depicted as a series of connections, lines and flights, envisioned by the authors as a valid variation to the standard, binary logic that has dominated Western thought.

By advocating the rhizome as a metaphor for ‘displacement’ within Khlebnikov’s poetics, I will elaborate on the scheme of the rhizome in terms of Khlebnikov’s notion of ‘the word as such’ (slovo kak takovo) as a poetic of displacement and the specific mythopoeia of Khlebnikov that is also one of displacement. In each of these areas, displacement has occurred as a diversity of forms of representation within the word; its related concepts are structured as a configuration of the language of possibility and of otherness central to his poetic experiments as depicted by the concept of the rhizome.

In the poetics of Khlebnikov, language is the very otherness that is a metaphor for displacement. The idea of displaced meaning – a displacement of a unified, autonomous meaning – is outlined in the following extract, where a dialogue between a student and teacher is created to convey the materiality of language in order to substantiate his own poetic excavations. (The dialogue itself is complete with meta-narrative; as it comments on the nature of this literary form itself, it is reminiscent of Plato’s dialogues and attempts to reconfigure the form of dialogues as we have understood them since Socrates, thus reintroducing the form to the avant-garde.)

The dialogue explores the role of words’ internal materiality, as the student is indignant that his philological findings demonstrate that the perimeters of meaning are within a word and are dependent on certain conditions. These conditions, as demonstrated by the internal variation of vowels, are diverse and not independent: they rely on what is both absent and present (as the student asserted with the example of a bald spot and a tree trunk). Conditions of language are exposed to conditions beyond what is present: in Khlebnikov’s poetic world, words have a displaced relationship to what they represent. There is an attempt to cleanse language of its unnatural, static and tired references, and reject the ‘common’ associations of words, which are an artificial and arbitrary construct.

Although this is somewhat speculative, the point can be made that Khlebnikov’s poetics of displacement may have been influenced by his probing into foreign languages. The idea of an ‘internal declension’ is nothing new in terms of Semitic languages. For example, this can be illustrated by the Arabic root verb ka-ta-ba (to read). If it is declined internally, it could mean kitaab (book), kaatib (writer), kutubu (books), etc. As short vowels are generally not written in Arabic, meaning is gathered by context. This visualisation of an internal declining system may have appealed to Khlebnikov, as the idea of visualisation was rather impertinent to Futurism and the absence of the vowel may have had an impact on him. Similarly, the presence of radicals and homophonous logographic characters in Chinese (symbols for words that sound alike but have different semantic meanings) may have also had an influence on the poet, given the ‘visualness’ of these languages.

From the play, Zangezi, Khlebnikov’s improvisations are realised by formulating words with the Russian root ‘um’ (‘mind’) in order to overturn both conventional and unconventional prefixes, affixing to the root word meanings that do not exist, but within the rules of language could be possible, thus displacing the meaning of ‘um’ as it is usually perceived. Khlebnikov’s linguistic developments also represent the possibility of becoming a poetic in itself – an otherness that exists within language. This displacement calls into question the notion of poetic language as a form, rather than as a substance – a protest against semantic conditioning. Like the rhizome, it is a system of relations, as any prefix in Russian can be applied to the root word.

In his notes on the play, Khlebnikov explains this elaborate system and what could essentially be seen as the destruction of a standard language as we know it. As if on exhibition, the root word begins to lack definition: with the prefix ‘v’, it is explained as ‘an invention’. Un-love of what is old leads to ‘vyum’. Or the letters ‘Go’ can be explained, as noted in the play, ‘high as those trinkets of the sky, the stars, which aren’t visible during the day.’ From fallen lords (gosudari in Russian) ‘Go’ takes the dropped staff. ‘Noum’ and ‘Daum’, with their common meanings of ‘No’ and ‘Da’ (‘but’ and ‘yes’ in Russian), signify the argumentative and the affirmative assigned to the mind. The mind is a key to refer to in terms of Khlebnikov’s poetics: the principle of Zaum, trans-sense, or literally ‘beyond-mind’ (za in Russian meaning ‘beyond’), is central to how the Futurists were informed and inspired by language construction and how word-creations existed as form and not only as technique, revealing unexplored norms of poetic language. Like the rhizome, the word ‘um’ is a world – and a word – unto itself.

Already, the life of the word – and the forms it could take – is the essence of poetry: an idea that could arguably be said to have formulated the poetics of Futurism. Significantly, this essence, the life of the word, is the key to the history of a people, which here could also be in opposition to the past, on in confluence with it – a life ‘detachable, connectable, reversible, modifiable, and [that] has multiple entryways and exits and its own line of flights’.3 The power of poetry is to unlock that life, which exists in opposition to the past as it is, and should be expanded and opened to the present.

The idea of liberation is central to the word – as a word was added to, expanded, it was liberated and displaced from the general constraints of what standard Russian allowed. It is not mere playing with language; in their translations of Khlebnikov’s notes and prose pieces, Vroon and Schmidt pay attention to the word experiments in his notebooks. They detail how a certain word was written down, creating ‘several neologisms based on the form of the word … adding a prefix, for example, or replacing one morpheme with another.’ As the following excerpt from the poem ‘Symphony of Love’ demonstrates, it is a vigorous attempt to try and challenge the boundaries – the tide of where and how language could go.

This manner of exploding and shattering the accepted parameters of language determined the path of future experiments. Khlebnikov’s scientific approach to language had been gestating for quite a while before he began collaborating with Kruchenih on the essay ‘The Word as Such’, where both writers tried to define the work of art as the art of the word: ‘прoизведение искусства – искусство слова’ [337].4 Moreover, Khlebnikov’s early creative works were already undermining certain expected usages of language – that is, they were displacing them. For example, in the poem ‘Incantation to Laughter’, the emphasis is on the word as the end ¬– not the means – to poetic creation. It is based on the common word of the Russian language, ‘laughter’, the root of which is given in multiple variations, appearing to conform to flexible rules of Russian word formation. This end product contradicts the rules of Russian, as the following forms of ‘laugh’ do not occur in standard Russian as they are formed here.

Written in 1909, ‘Incantation to Laughter’ is one of Khlebnikov’s most anthologised poems. This is a literal representation of the concept of the inner life of the word, buoyantly similar to a classroom exercise in alternative word formation. This poem is an experiment that tries to get back to the root meaning – its ‘arche-’ – of the word, or perhaps in more philosophical terms, to see and hear the word as the thing in itself. But in trying to go back to the origins or the ‘arche-’ of sense, this play with word formation also points to new projections of sense: a multiplicity of projections, a series of events in the formation and becoming of the word, pointing to the ‘future’ of the word. In order to create and be a part of the future, language also had to look back at itself. It also had to look as far back as possible, to its root, to its pre-linguistic forms outside of verbal language – a temporality that transgresses the authority of language, a mythopoeia of symbols and visual images at the poet’s disposal.

In fact, this poem connotes something rather non-verbal yet human: a laugh. And, within this breathless usage of different prefixes, and the creation of nouns and verbs from the one root, we are exposed to a passionate dedication more pronounced than any notion explained in the manifestos produced by the Futurists. Predictably, there is no classical metre used here; rather, it is a classic example of displacement as poetics, as something not mystical, but instead a linguistic element possessing the potential to become poetic. It also demonstrates that language is still not fully formed, neither syntactically nor semantically, and that the possibility of a possible ‘original’ reading of language could be undertaken and performed. Unlike Wittgenstein’s and Peirce’s theory of the sign as being arbitrary and subject to change within language, Khlebnikov attempts to assign some ‘original’ meaning to different phonemes, letters, and words, as his work is consumed with origins, and it will be explored in this article how Khlebnikov’s poetics are a displacement of those origins taken for granted within language, speakers and myth.

This view of the face expressed piece by piece in the poem discussed above, ‘бобэоби пелись губы’ is characteristic of Futurism in general, and especially Cubo-Futurism. This ‘canvas of such correspondences’ in the poem reflects a general rejection of mimesis, a distorted sense of perception deeply established within many different trends of Modernism in different parts of the world. For example, in the paintings of Natalia Goncharova, Pablo Picasso, and Joy Hester – three artists who represent three very different trends of Modernism – there is a dissociation of features on a canvas that we have known to be indissolubly united while on the human face. In Khlebnikov’s poem, ‘бобэоби пелись губы’, the face is made up of features that are sung into existence, a canvas created by accidental correspondences. Khlebnikov’s words themselves also become visual images: his theory of phonosemantics is related to how the letter is formed visually, as outlined in his essay, ‘Artists of the World’. In the essay the artist’s task is to conceptualise and create the alphabet as a spatial world, imagined by Khlebnikov as a body made up of different parts, and to ‘provide a special sign for each type of space … to designate ‘m’ with blue, ‘v’ with green, ‘b’ with red, ‘c’ with grey …’ The language of Khlebnikov’s poetic principles is a soundshape based on phonosemantics that cause synethesia.

Phonosemantics, as a branch of linguistics, is concerned with the notion of phonemes carrying a meaning within the written and vocalised form of the phoneme. Although in Saussarian and Chomskian linguistics there is the conviction that there is no correspondence between meaning and linguistic sign, and that semantics is abstracted from language (and the people of that language) itself for Khlebnikov, abstractions within language could not exist. Instead, like the rhizome, there could be networks and correlations of possibility. It is necessary to note that linguist Roman Jakobson in his book The Sound Shape of Language delves into the effect of form on content in poetry and, in his analysis of a poem by E.E. Cummings, notes that content and form (and especially, the sound shape) could not be clearly distinguished, and definitely not abstracted. Phonosemantics is the study of linguistics where parole is not subordinated to langue, and in Khlebnikov’s poetic treatises and creative works, we see that the phoneme carries a meaning rooted in its utterance, in its articulation – it is rhizomorphous, threatening to spill over with the fact that the linguistic sign is in fact not only not arbitrary, but polyphonic in articulating a possible meaning that may ordinarily be absent from the space of the word.

Although Khlebnikov is associated with Futurism in terms of always ‘making something new’, he was simultaneously also outside their framework as his Futurist inventions do not by any means entirely reject the past or demonstrate the desire to do so given the interrelatedness with the word and its connection to a people, their history, and the possibility of exploring and exploiting those meanings inherent within language. Although he was connected with a collective of artists who propagated the seeds of ‘newness’, Khlebnikov was not entirely subscribing to the following aesthetic trends either, which was a declaration of replacement, and not one of displacement.

The Khlebnikovian world is a trans-realistic world, complete with temporal scenes that displace the present, lack coherence, and are based on a systematic set of relations in which utopian futures and the destruction of the utopian past affirms the rhizome’s fascination with multiplicity.

Khlebnikov’s works lack linearity – they are not grounded in a model of chronology. Their structure thus corresponds to the crux of the rhizome, which has a diffuse relationship to temporality. According to the rhizome, which is a relational structure, and hence grounded in a distant simultaneity, time has no barriers – accelerating into the future and the past simultaneously. Mythological and historical figures and motifs such as Peter the Great, Marx, Zarathustra, Leila and Majnun, mermaids, Perun, Kava, Tzo-kabi, Jesus Christ, Shiva, Khrishna, Ra, Darwin, and self-catering tablecloths from fairy tales, as well as events and people from his surroundings, are drawn on to create something new: the future which can only be made by convoluting with the past. History is merely a façade of representations, where a word is inscribed as discourse, as form and content, where form has meaning. Khlebnikov’s conception of history repudiates linearity, and has been identified as ‘genealogy’ by Foucault. Likewise, the past can only be understood via the future, and thus, displacing time itself by endlessly contrasting, comparing and melding various periods of time – a poetic map of epic scale.

In Khlebnikov’s works, the word must always refer to what is not: consequently, his use of time and figures, which personify a particular timeframe, are also subject to the wide semantic shifts of time and space according to his principles where there is combustion of archaic and modern, of art and science, thus producing new calculations (and creations) of time. In explaining the relations between the birthdays of Virgil, Dante and Goethe, Khlebnikov reduces these figures to a mathematical unit – to a ‘Law of Generations’ as the essay is called, as the time that separates these famous people is reduced to a formula that has the potential to create language. It is a mere accident of parachrony that Leonardo was born in 1452 and Euripedes in 490 BC – the correlating factor is the time and space that inhabits them, as the epochs associated with these figures have been opened up and released into another world of signification.

In his essay titled ‘Proposals’, he also emphasises the need to restructure perceptions of time. Instead of war taking place within geography and space as we’ve come to understand war over time, instead we should come to an understanding of a war between time, that is, between generations. Time becomes a space that can be fought over and, within the Futurist conception of utopias, may even be conquered.

Admittedly, Khlebnikov’s originality regarding time was a key concept central to Futurist poetics. There was a general investment in a farcical time of history, when utopias – cosmic and linguistic – seemed entirely probable. In the desire to dismember one’s art, the world and the art of ‘seeing’ are central to Futurism. Futurism also represents a penetration into time: an expansion and violence that goes beyond the timed rhythm of the lyric poet prior, as ‘the body is no longer itself [. . .] a privileged object’ of representation, and this can be seen as a metaphor of how time is beyond representation in Futurism.

There is something persistent in this tone, an extreme desire for a new aesthetic almost apocalyptic and sublime in nature. Yet Khlebnikov didn’t reject these mystic ideals and, in fact, continued a mythological lineage by creating and adapting Futurist principles. Khlebnikov’s poetics are far more speculative than his contemporaries in style, producing a poetics where time is constantly displaced, referring to another time, knowing no borders, no ruptures and formulated by a profound, systematic movement.

An example of time exposed to and altered by space is found in the narrative play ‘Zangezi’. It is composed of three language forms expressive of Zaum: bird-language, star-language and gods-language, which portray a sense of endlessness. The play encapsulates many cultures and languages, underscoring the discord that arises within this cacophony – hence its timelessness. The space of life is conceived of as being at one with that of the dead – infinite and without end like Khlebnikov’s ‘zvukopis’ or the rhizome, as space is constantly exposed to the possibility of its own otherness.

In the poem ‘Asia’, the present moment refers to the past and back again to the present. It is addressed to a ‘you’, who appears to be an allegorical female who partakes in a performance of language, turning the pages of her own history with an invisible finger. The ink is ‘human’, a metaphor connected to the previous metaphor of the anonymous person in the poem: a mere human who is enslaved to the history of the book in front of her. This slave also carries tsars on her skin as if they are beauty spots (rodinoy tsarei); like ink, the tsars have also made their mark, but their mark is indelible.

This poem is a stirring foray into how linguistic symbols themselves can connote history, especially for someone whom we may assume is illiterate (she is also turning these pages, not reading them). The historical significance of the assassination of the tsar deserves a shocked symbol of punctuation; armies are commas, the crowd a field of dots, and people’s anger bracketed by the gaps of centuries. Punctuation is visualised as a language; it is an object that is an end, and again, not a means. Thus, history is equated to syntax entwined at the meta-level of the poem: it is both the form and the content of the poem.

Despite their bursting energy, as exemplified by Marinetti, the Futurists were still involved in a dialogue with history, with the ‘West’, and with institutionalised forms of literature. Even in opposition to those institutions, they still inhabit them. Their heady aspirations to dispose of/with such traditions, as stated in the collective manifesto ‘A Slap in the Face of Public Taste’, emerges as an ideal that is also rather self-contradictory.

As outlined in the analysis thus far, Khlebnikov himself negated these ideals – relying upon known motifs and figures from Pushkin, creating adjectives from Dostoyevsky’s name, and relying upon folk motifs in his poetic world. It is worth noting that Pushkin’s language is also made foreign: an allegory of the uselessness and exotic form of a hieroglyph. It is also a textbook foray into the ‘arche-’ of language, an experiment which tries to get back to the root meaning – the ‘arche-’ – of the word, or perhaps in more philosophical terms, to see and hear the word as the thing in itself. This is quite similar to the endeavours of Khlebnikov and Kruchenih in the essay ‘Our Foundation’ as well, as was also demonstrated in the previous excerpts from Khlebnikov’s essays ‘Teacher and Student’ and ‘Artists of the World’. Letters of the alphabet – in this case, the vowels – are devised as forms that exist as a source from which poetic language can spring.

However, there are some differences too, as Khlebnikov and Kruchenih were attempting to outline the structure of азбучных истин (‘alphabetic truths’) – in other words, the truisms of consonants. And, unlike Burlyok’s, in their use of metonymy, they attempted to create a system to break or reduce the letter itself down to its pure form. Словотворчество (‘word-creation’) should be a language where the unit of a letter itself is deregulated. It is a disembowelment of all associations, thus developing a science of the letter. Writing during the period of Futurism, critic Tastevan is convinced that the governing principle of Futurism is ‘word-creation’, although in his view it is a continuation of Mallarme’s notion of the mystique of the word, and therefore, fails to break from literary history.

This pre-occupation with the base of the word – that is, the letter – to transgress the boundaries of language in order to critique it and the nature of the word, is evident in the next poem by Kruchenikh. The harsh vowel sounds in the poem, which signify a foreigner’s speech in Russian, is in a sense, Zaum, as it is a display of what Khlebnikov deemed as ‘word-creation [that] is an explosion of language’s silence, the deaf and dumb layers of the language’. Thus, Kruchenih’s narrator is drawing attention to the vowel sounds in typical Russian. It is creating a non-standard form of what Russian poetics is capable of, spawning a poetic language full of dissonance.

To the ordinary ear, the vowels fall far from standard poetic metre, as the words themselves define concrete meaning here, the ear is left unsure of how this construction adheres to how meaning is usually made. Like Kruchenih, Ilya Zdanevich also explored vowel sounds in the poem, ‘Ослиный бох’ (‘Oslini Bokh’), returning language to its inner flesh, and likewise becoming foreign in the process. The mono-syllabic vowels are a form of the word coming into being; language is not fully formed syntactically or grammatically, despite the fact that the language itself is a form that connotes something.

These vowel sounds also seem to be heraldic – this extolling force building up towards something sacred and mighty (god?) at the end. It is an amalgamation of high- and low-culture, as kakarus is rather close to the verb kakat (‘to do a poo’ – a play with words that Gogol uses for the hero in ‘The Overcoat’), referring to baby-talk or childlike rhymes, a principle of Futurism rather reminiscent of Bakhtin’s Carnival. Language is not used to denote; it itself is a denotation, hence the fascination to sweep away the dust from its pedantic, stale, institutionalised forms, and to bring it back to the culture of the people – whether they speak literary Russian or not. Language has turned full-circle on itself, subverting how meaning – poetic meaning – is made.

Indisputably, Futurism unyieldingly uses language to challenge the Judeo-Christian ideal that in the beginning was the word, and the Platonic idea that ‘Man is a being of the word’. The word is much more sacred and obtuse for the Futurists, demonstrating ‘the inherent power of the word stemming from its sacred origins, because of the knowledge that surfaces when thick layers of semantic convention are brushed away’. It is an eternal search for the sincerity of the word – where language is language only, ideally immune to human agency. The ensuing excerpt from Kruchenikh, assembling the most difficult sounds of Russian, is a work of genius that the poets believed to surpass the genius of Pushkin.

Khlebnikov was convinced that the future and past, together, were keys not only to the core of language, but also to human identity. Khlebnikov’s ideas regarding language, identity and culture displaced the aesthetic that he was to become a part of. The next extract reveals the vastness that facilitated the creation of his own brand of poetics within the artistic trend he found himself working within.

In the ideal world of Futurism, humanity will be looking forward, moving forward, and will be connected to that internal world of humanity. For Khlebnikov, that internal world is inseparable from the word, which is connected to the world: that world constituted of many cultures, languages, time frames and spaces. With reference to time and space, the East is a source that Khlebnikov refers to time and time again, in order to replenish these notions. In the poem, ‘The Oak of Persia’, Marx (a Western economist), jokes with Mazdak (a fighter for social equality during the Sassanid empire), in what is supposed to be 20th-century Iran, a comely kinship that is then contrasted with the pack of wolves in the background of the scene. Given the larger stock of Eastern motifs in the Persian poems, there is ‘transference of time and the spirited exchange of people and events from one period to another, resuscitating old myths with new meanings’.5

Khlebnikov’s own utopian dynamism as a poetics of displacement is energetic in a way that distinguishes his works within this canon of Futurism. The analysis of his Persian poems, boundlessly immune to the staid dichotomy of East and West, are also a space of the world (and the word) that Khlebnikov displaced. This displaced space inevitably undermines the system of poetic language and motifs, as the role of the ‘speaking subject’ is one that is inevitably divided, as the ‘Other’ cannot be eliminated from poetic discourse. Like the rhizome, the speaking subject is necessarily divided and, as expressed within Khlebnikov’s poetics, is caught within a network of desire where continual transformations redefine the terrain of language, metaphor and notions of the self. The speaking subject is a metaphor created by leaps of associations and what would at first prove to be seemingly unconnected relations: a metaphor of displacement.

Notes

- Vygotsky, Lev.S. Thought and language. Ed. Alex Kozulin, Trans. Eugenia Hanfmann and Gertrude Vakar, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press ,1986).

- s. Alan Sheridan. (New York: Norton, 1998), 73.

- G Deleuze & F Guittari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. B. Massumi. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1986), 21.

- V. Khlebnikov. The Collected Works. In six volumes. Ed. R.V. Duganov. (Moscow: IMLI RAN, 2006), vi-2; 337.

- P.I Tartakovsky. Russian Poets and the East. Bunin. Khlebnikov. Yesenin. (Taskent: Publisher of Literature and Art in the name of Gafura Gulyama,s 1986), 175-6.

Bibliography

Barooshian, V.D. Russian Cubo-Futurism 1910-1930. A Study in Avant-Gardism. (Mouton: The Hague, 1974)

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhailovich . The World of Francois Rabelais and Folk Culture in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Moscow: Creative Literature, 2000)

Burlyok, David. Veseniy (Moscow: 1915)

Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Trans. Brian Massumi, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987

Foucault, Michel. ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’, Ed. James D. Faubion, Trans. Donald F. Brouchard and Sherry Simon. Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984, vol. 2 (London: Allen Lane, 1998)

Grigoryev, ; ‘The Word and Myth-creation’, Budetlyrnin: Works dedicated to the creativity of Velimir Khlebnikov

Jakobson, Roman & Waugh, L.R. The Sound Shape of Language. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1979)

Khlebnikov, Velimir, Creative Works., Ed. M.Y. Polyakov, V.P. Grigoryev, A.Y. Parnas (Moscow: Soviet Writer, 1986)

Selected Works., Ed. Ronald Vroon. Trans. Paul Schmidt (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997)

Collected Works., Ed R.V. Duganov (Moscow: IMLI RAN, 2002-2006). In six volumes.

Kandinky, Vassily. Trans. F. Golfing, M. Harrison & F. Ostertag. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz. 1947)

Lacan, Jacques, Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Trans. Alan Sheridan (New York City: W.W Norton and Company

Lacan, Jacques, Ecrits, Trans. Bruce Fink (New York City: W.W Norton and Company, 2006)

Marinetti, F.T. ‘The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism’, Theories of Modern Art, Joshua E. Taylor, trans. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968)

Nicholls, Peter. Modernism: A Literary Guide. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995)

Nietzsche, Frederich. The Birth of Tragedy, Trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1967)

Rogorev,E.C. 20th century Russian Literature. (St. Petersburg: Paritet, 2000) p.118.

Steiner, George. Language and Silence (Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin, 1979)

Tartakovsy, P.I., Russian Poets and the East. Bunin. Khlebnikov. Yesenin. (Tashkent: Publisher of Literature and Art in the name of GafuraGulyama,1986)

Tasteven, Henry, Futurism: on the way to a new Symbolism (Moscow: Iris, 1914)

Vaslieyev, E, The Russian Poetic Avant-garde of the 20th century, (Yekaterinburg: Ural University Press, 2000)

Vroon, Ronald, ‘The Poet and His Voices’, Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov. Volume III

Vygotsky, Lev. Thought and language. Ed. Alex Kozulin, Trans. Eugenia Hanfmann and Gertrude Vakar, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press ,1986.)

Zdanevich, Ilya, Yanka krul albanskiy (Tbilisi: 1918)

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar